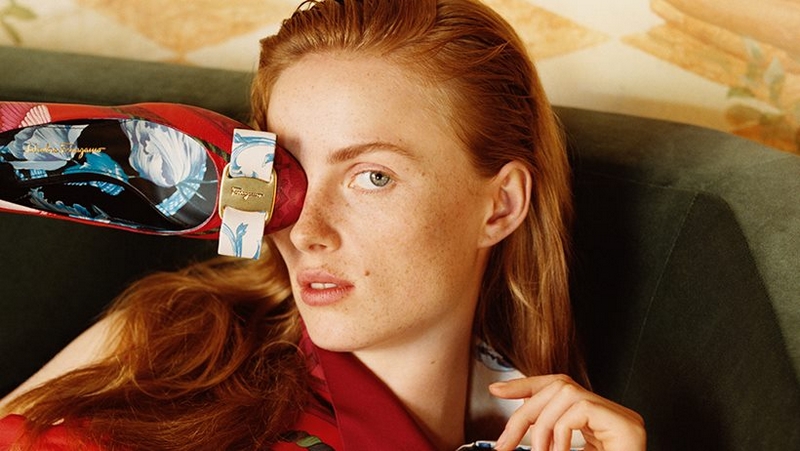

This is a Cinderella story, with a twist. In 1940 the great shoemaker Salvatore Ferragamo, 42 years old and at last successful, combed Italy for a suitable wife. He was no prince – he had slogged his way out of deepest rural poverty and survived reversals of fortune. What he knew about was feet, and how they should be shod.

On a visit to his home town, Bonito, in southern Italy, to disburse charity funds, he met the mayor’s teenage daughter, Wanda, 23 years his junior, and instantly determined to marry her. He asked if she would take off her shoes so he could demonstrate a podiatric point to her father, who was also the local doctor. Salvatore was charmed by the toe that peeped through a tiny hole in Wanda’s stockings and sent orders to his cobblers to make her not glass slippers but super-light black suede brogues, an inspired gift in wartime Italy, short on shoe materials and transport. The couple were married three months later.

Salvatore’s assessment of the strength and practicality of his bride’s character was proved right when he left her a widow in 1960. She took immediate command of his enterprise and evolved it from a modest craft business into a serious luxury goods brand. Wanda Ferragamo, who has died aged 96, was the company’s CEO for more than 20 years, president and chairwoman for decades, and worked daily in her office almost to her end, briskly deciding policy and personnel: “It takes me five minutes to see if something is wrong.”

Wanda, daughter of Fulvio Miletti, had no training for the work, having been educated, like her mother (who died when Wanda was 16), to be a cultured wife. That was her role from 1940 to 1960: she bore Salvatore six children and established the family at a Renaissance villa near Fiesole, outside Florence, where they were prospering when Salvatore died, aged 62, from cancer.

His firm was the perfect Italian model of a designer-craftsman employing specialists, handmaking goods for famous customers. Salvatore had earned his reputation for imaginative yet comfortable footwear in the 1920s and 30s in Los Angeles, where his customers were movie stars who stayed faithful when, after 13 years in the US, he returned to live and work in Florence.

At his funeral, the workers promised Wanda they would help sustain the firm, so she followed the old craft guilds tradition of the boss’s widow taking over management of the business. At home Salvatore had always discussed with her his plans, clients and ambitions, right down to the details of experimental soles and heels. Nobody else knew as much about the business as Wanda had learned by watching and listening. She arrived as La Signora, ultimate power at the firm’s Florentine headquarters in the antique Palazzo Spini Feroni, just as fashion became a major Italian export.

Her first decision was to appoint her daughter Fiamma, who was then 19, head designer. Fiamma had inherited Salvatore’s delight in shoes, and he had encouraged her talent. Wanda saw that craft supremacy in shoes would no longer be enough for fashion. There had to be other goods: matching handbags, then the silk scarves that were a national speciality (this division was the creation of another daughter, Fulvia) and eventually garments.

The firm’s personal service and its contracts with grand international stores were supplemented by new Ferragamo boutiques in the smartest shopping venues. Within 20 years, shoe production had increased tenfold, yet the firm coolly ignored the industry’s efforts from the 1980s to move factory production offshore, and continued to make its wares in Italy. The family fidelity paid off, as new customers for luxury wanted, as near as could be found, Salvatore’s original materials and technical skills.

As they grew up, Wanda’s other children, Ferruccio, Giovanna, Leonardo and Massimo, joined the management, all earning the same income. Only three grandchildren were admitted to the firm, although Wanda kept her more than 70 descendants informed about the business. Those strict limits, and tough choices in hiring, protected the company from the curse of “clogs to clogs in three generations”, and Wanda rejected buyout offers for decades. She stood down from the chair in 2006, but supervised the first public stock offering in 2011, and afterwards headed a foundation to fund and train artisans, remembering Salvatore’s earliest struggles.

Wanda was authoritative without grandeur, acute, perpetually up to date, and she retained the elegance Salvatore had admired on their first encounter. (She always wore the 7cm heels he had decided, on sight, were right for her stance.) Of her many awards, she was proudest of being made honorary OBE and Cavaliere di Gran Croce.

Fiamma and Fulvia died before Wanda; her other children survive her.

• Wanda Miletti Ferragamo, businesswoman, born 18 December 1921; died 19 October 2018

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.