The first auction dedicated to the library of Pierre Bergé achieved a total of €11,687,380 at Sotheby’s auction. The sale offered a stunning selection of 182 works of literary interest spanning six centuries, from the first edition of St Augustine’s Confessions, printed in Strasbourg circa 1470, to William Burroughs’ Scrap Book 3, published in 1979. Among the top lots were Flaubert’s L’Éducation sentimentale which sold for €587,720 and Louise Labé’s Oeuvres, one of the most magical books from the French literature that achieved €524,845.

The thematic sales which will follow in 2016 and 2017 feature not only literary works, the core of the collection, but also books on botany, gardening, music and the exploration of major philosophical and political ideas.

On an evening when Anonymous were berating the 1% in Trafalgar Square, I was in a book-lined salon a short distance away with a man who has spent a lifetime dressing the wives of le premier cru. Pierre Bergé never actually had pins in his mouth himself, you understand – that was his lover and partner, Yves Saint Laurent. But Bergé was the cool maitre d’ who kept La Maison YSL running on castors while the maestro was in the back, agonising over his sketchpad.

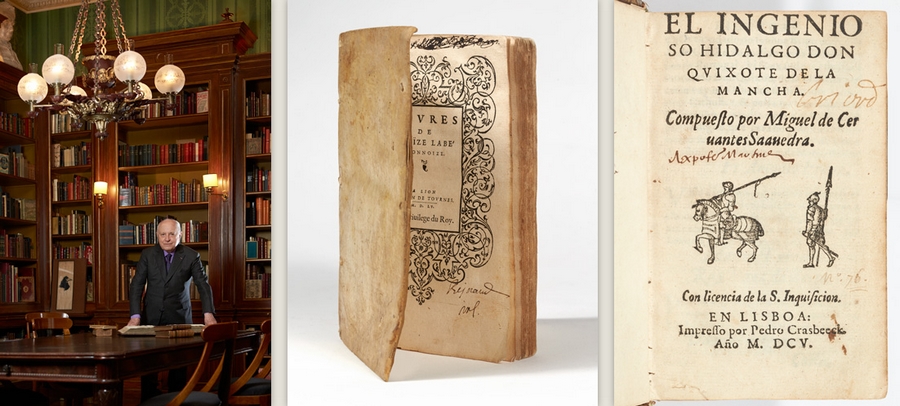

“Fashion is not an art,” says Bergé, “but it takes an artist to make fashion.” The 84-year-old unburdens himself of this apothegm with the foxy charm of the late French actor Charles Boyer. He is wearing a dark brown suit by Anderson & Sheppard, the Savile Row cutters where he has been going for 30 years, with the discreet blazon of the Légion d’honneur in his bespoke lapel. As for the book-lined salon, we are surrounded by his “jardin secret”, he exhales raptly: the most priceless and exquisite library in private hands, grown from 1,600 vanishingly rare and hysterically hard-to-find books and manuscripts.

Bergé has decided to part with his beautiful specimens and the auctioneers handling the sale have put an estimate of almost £30 million on them, making this perhaps the most valuable collection ever to come to market. It includes early editions of books which are cornerstones of western civilisation: a first edition of St Augustine’s Confessions printed in Strasbourg in 1470 and estimated at up to £140,000; Dante’s Divine Comedy from 1487; Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories and Tragedies printed in London in 1664. Coddled by gloved flunkies in dehumidified rooms, these volumes have been cherished with the same hushed attention that Saint Laurent and Bergé once lavished on Parisian ladies of a certain age.

Together, Bergé and I admire a heavily worked manuscript of The Sentimental Education by his favourite, Flaubert, published in 1870 and valued at up to £420,000. Naturally, he also has a copy of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary: it has the author’s handwritten dedication to Victor Hugo on the flyleaf. He adores connections like these. He has a volume by Baudelaire dedicated to Flaubert, and his copy of Treasure Island (1883) is not only a first edition, but a present from Robert Louis Stevenson to a friend who suggested the character of Long John Silver.

The eminence grise of the rag trade shows me an illustrated copy of The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe. “I don’t like Poe so much, but this was translated (into French) by the great Mallarmé and the art is by Manet,” he says. Briefly released from a vitrine for our delectation are the fragile, handwritten notes for the Marquis de Sade’s last erotic novel (all that survived the fastidious bonfire lit by the Marquis’s scandalised son). These provocative jottings, composed on paper as dry as the leaves of an old cigar, could set you back £280,000. In addition, la Bibliothèque de Pierre Bergé boasts super-rare early copies of classics by Cervantes, Joyce, Bronte, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and more. They were acquired by Bergé himself and “his agents”, to a strict formula that only books by authors he admired were admitted.

It was literature that gave the young Bergé his lucky break, although this good fortune was at first well disguised. On his first day in Paris, as he was strolling the Champs-Elysées, a Surrealist poet called Jacques Prévert fell from a window and landed on top of him. A winded Bergé chose to see this defenestration as an augury that the French capital had been waiting for him. He embarked on a career in antique books, truffling for overlooked treasures among the bouquinistes, the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine. In the brilliant young tailor Yves Saint Laurent, he recognised another man with an eye for a silver lining. “Christian Dior fired him, and on the same day, he told me we will set up our own business, the house of Yves Saint Laurent.”

Before long, the pair were dressing the screen goddess Catherine Deneuve. The spouses, and mistresses, of the rulers of the Fifth Republic soon followed. Twice a year, in readiness for YSL collections, the designer and his major domo repaired to their villa in Marrakech. They had another home redecorated to a theme of Proust’s À la recherché du temps perdu, the one literary interest they had in common. “It was the only book he ever read,” says Bergé. “Of course, it is a very long book.”

The couple amassed an art collection to excite the salivary glands of gallery directors and oligarchs, including works by Matisse, Cezanne and Klimt. The anguished genius and his suave helpmeet, walled in by Old Masters and first folios – it recalls A Rebours, Joris-Karl Huysmans’s great novel of decadence, of which Bergé naturally owns a highly covetable first edition. The pictures were sold after Saint Laurent’s death in 2008, fetching more than £240m. When asked if he would miss them, Bergé replied, “Everyone dreams of attending their own funeral. I am going to attend the funeral of my collection.”

“It must have been an exquisite life,” I suggest. But Bergé hasn’t devoted himself to the luxe, calme et volupté [luxury, peace and pleasure: Baudelaire] of the super-rich without developing a keen nose for how fashions change, swiftly and fatally. “I don’t care to look back,” he says insouciantly.

Bergé claims that Saint Laurent’s great insight was to remove couture from chic restaurants and fashionable apartments and take it “to the street”. The fashion house “empowered” women by putting them in men’s tailoring, in the broad-shouldered shape of the marvellously franglais le smoking. The stress of bringing YSL’s creations before the public and the fashion press took its toll. The couple’s intimate relationship ended in 1976, though they remained friends and business partners.

Today, haute couture is finished, snorts Bergé at his most gallic, no more than a licence to flog scent and handbags, and a pastime for bored supermodels and cashiered pop stars. Only in France, perhaps, could a man with his profile have been a fundraiser for those well-groomed socialists, François Mitterand and Ségolène Royal. I invite Bergé to run a couturier’s tape measure over our own ruling elite. He approves of David Cameron’s holiday wardrobe, but he is not an admirer of the prime minister. He says of Jeremy Corbyn: “I like him. He is a dreamer – and without dreams you have nothing.” But as he claps eyes on a picture of the Labour leader in shorts and dark ankle socks, he shudders almost imperceptibly, like a sequin shaken by a distant Métro.

Our tête-à-tête at an end, Bergé musters his entourage of stubbled younger men who are dressed in autumnal tones. They’re going on to a party. “On y va!” he instructs, leaning dapperly on a cane.

- La Bibliothèque de Pierre Bergé was auctioned at Sotheby’s, Paris, on 11 December. His interview with Stephen Smith appears on BBC Newsnight later this month

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.