After Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 disappeared on 8 March last year , one of the most vexing questions was: how can a modern aircraft with 239 people on board vanish without trace?

Tom Walkinshaw believes a repeat could be avoided by tracking planes via a network of hundreds of tiny satellites that monitor oceans where there is limited radar coverage.

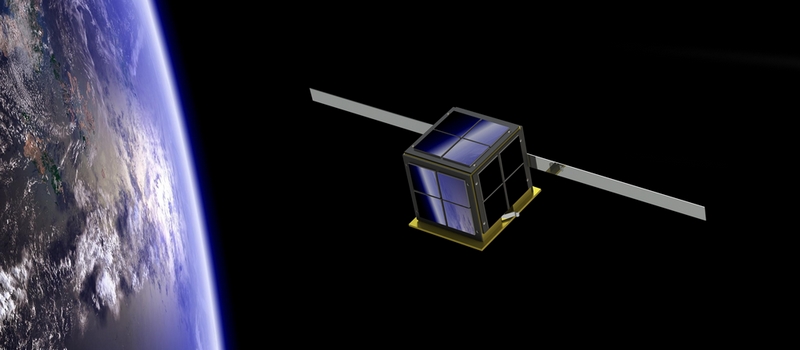

The 25-year-old founder of the PocketQube Shop, a Glasgow-based company which provides the components for making tiny 5cm³ PocketQube satellites, is taking advantage of a new generation of space technology that allows small businesses to join an industry previously the preserve of governments and well-funded private companies.

Dubbed ‘NewSpace’, this fresh market is based around technology which would have previously been prohibitive in cost. Now it can be bought off the shelf and small satellites like those sold by Walkinshaw can be launched into orbit at a price unthinkable in previous decades.

Corentin Guillo, the head of missions at the Satellite Applications Catapult – one of the UK government’s centres for fostering innovation – said technology used in mobile phones and laptops can now be used in small satellites. This in turn makes them more disposable than their predecessors, which were typically large and lasted for more than five years. The new generation of satellites – like the PocketQube and the 10cm³ CubeSat – also offers a common platform.

“Almost nobody builds their own satellite standard anymore – it doesn’t make sense to re-invent the wheel when there are several incredibly powerful, commoditised open source options,” said Guillo.

The miniaturisation of technology allows people to do more with less hardware, said Chad Anderson, the managing director of Space Angels Network, an investment house specialising in the space industry. That industry, he said, was worth $300bn (£200bn) last year. Constellations of smaller satellites, like those suggested as tracking devices for planes over oceans, are now a possibility.

“The launch costs are coming down and people leveraging today’s technology are able to do more with less and launch less mass to orbit. The price point has come down to where start-ups and entrepreneurs can really make an impact on the scene for the first time,” he said.

Costs to build and launch a satellite vary widely – paying by kilogram is used as a rough metric – but a CubeSat can be launched for around $200,000 (£135,000), said Guillo, compared with millions of dollars previously. Walkinshaw said a basic PocketQube can be launched for £20,000. While these figures may seem substantial, they are a fraction of what it would have cost in the past and opens up space to a wealth of new players.

“The absolute cost of doing it can be quite low now and you can buy the bits to build the satellite for a few thousand pounds sometimes. Then it just comes down to the manpower to put it together,” said Doug Liddle, the head of science at Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL), which has championed off the shelf satellites since the 1970s.

“We are at the point where we are seeing this explosion. We all rely on our sat navs, satellite television and broadband from space if you are in the middle of nowhere. But we are moving into a new era where it is … going to be that value added stuff on top. It is people making use of the sheer amount of data to solve big data problems, number crunching, doing the things we have seen in films,” said Liddle.

Uses for the satellites vary widely, from tracking tankers which have been taken by pirates to spotting violations to council planning permission rules via softwarethat pinpoints changes in buildings. While in the past these images were difficult to source, now the cost has decreased dramatically and is in some cases free, said Anderson.

Among the more imaginative uses for data gleaned from space has been by hedge fund managers in the United States who have examined the number of cars outside retailers such as Walmart to give some indication of the health of the company ahead of results being announced. In Britain, Geospatial Insight uses satellite data to estimate the limits of flood damage for insurance companies while Swindon-based AgSpace can identify the quality of crops for farmers by processing images of large swathes of land.

Craig Clark, the founder of Glasgow-based Clyde Space, which makes components for CubeSats, said the advantage of small satellites is that it is possible to have 200 at different orbits which can take pictures every five minutes. This means that if an area is cloudy, images can be taken at a different time in order to produce a clear image. “You can see how that type of system becomes very attractive for so many different applications,” he said. Glasgow has become known as a hub for the UK’s space industry, in part due to the strong space departments in the University of Strathclyde and the University of Glasgow, said Clark.

Where problems can arise is when the satellites are launched into space, typically as secondary cargo on rockets. In some cases, palettes of CubeSats are put on a shuttle going to the International Space Station and then offloaded by astronauts when they have the time, said Guillo. However, if the rocket on which the satellites are booked is delayed, they have to wait until the launch is rescheduled.

“It is like chartering your own aeroplane – you have got to pay full price. If you buy a ticket you go where it is going. It is the exact same with the rideshare industry in space,” said Walkinshaw.

- You can read our archive of The innovators columns here or on the Big Innovation Centre website where you will find more information on how Big Innovation Centre supports innovative enterprise in Britain and globally.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.