The exhibition Southern Geometries, from Mexico to Patagonia at Fondation Cartier in Paris celebrates the wealth of color and diversity of styles in the geometric art of Latin America, bringing together 250 artworks made by over 70 artists from the Pre-Columbian period to present.

Southern Geometries, from Mexico to Patagoniar; photo: fondationcartier.com

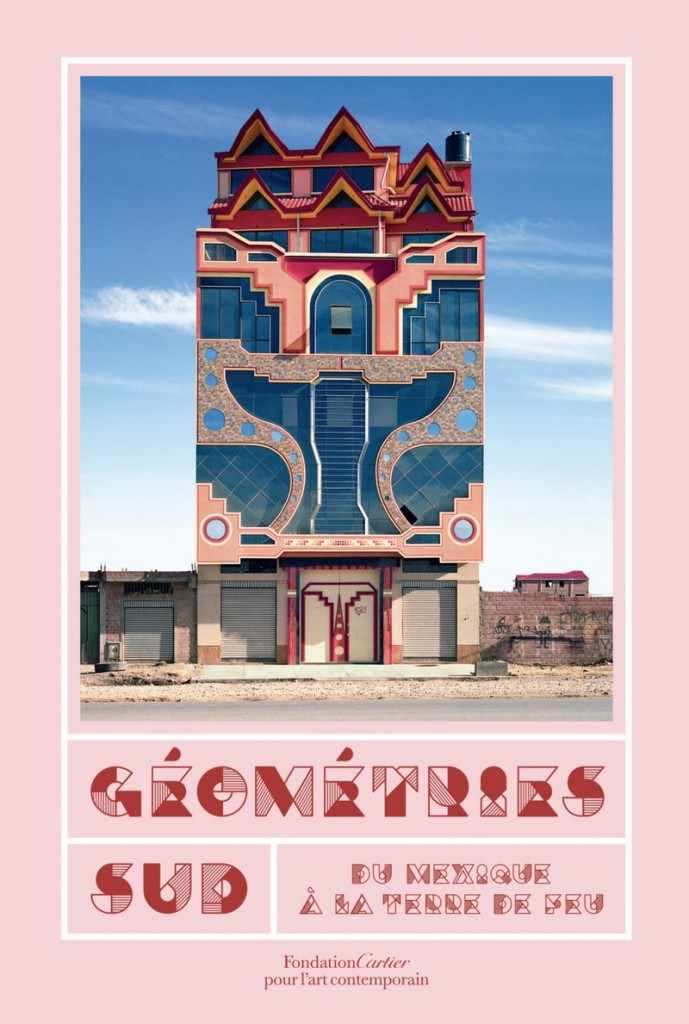

A bright green sunburst rises above the entrance to a building in El Alto, Bolivia, its mirror-glass rays tapering out to meet a yellow ziggurat-shaped pediment, beneath a momentous circular window. Polka-dot pilasters climb either side, zig-zagging this way and that, before terminating in an elaborate cornice, the whole ripe confection crowned with a surreal pitch-roofed chalet.

It looks like a one-off party palace, but turn the corner and you see several more of these things marching down the street in eye-searing palettes of reds, pinks, blues and greens, as if an army of building-sized slot-machines had taken over the city.

These psychedelic layer cakes are the work of Freddy Mamani Silvestre, a maverick builder-turned-architect who has spent the last two decades developing a suitably dizzying kind of architecture for the highest city in the world. He has now completed more than 100 buildings in El Alto, a million-strong conurbation that sprawls across the 4,000-metre-high Altiplano above the capital of La Paz, and garnered global attention for his startling vision of Las Vegas in the Andes.

An unlikely slice of this trippy, high-altitude world can now be seen glowing through the windows of the Cartier Foundation in Paris, where Mamani has erected a fantastical rainbow ballroom as part of a new exhibition on Latin American art and architecture: Southern Geometries, from Mexico to Patagonia.

“It might look like Vegas, but it is all grown out of our pre-Colombian roots,” says the 47-year-old, standing paint brush in hand beneath a gigantic crystal chandelier, as he puts the finishing touches to a candy-striped octagonal column. He says the layered cutouts in the ceiling refer to the Andean “chakana” cross, while the geometric frieze alludes to motifs found in Tiwanaku, the centre of the pre-Inca civilisation near El Alto.

But perhaps the clearest inspiration for his kaleidoscopic vision is the aguayo, the brightly coloured woven cloth of the Aymara, the indigenous group of which Mamani is part, which revels in complementary contrasts of pink and green, purple and yellow, shot through with zig-zag patterns. “My designs are a modern expression of our culture,” he adds. “Since Evo Morales [who is also an Aymara] became president, things have changed a lot. We feel proud of being Aymaran.”

The fashionable Parisian venue for Mamani’s first ever project outside Bolivia is a far cry from his beginnings. He grew up in a mud-brick house in a remote rural area, where he had to walk for an hour to the nearest school. As the eldest of seven children, he took charge and moved to El Alto with his brothers and sisters when he was 13, beginning to work as a mason, and later studying construction at university. He graduated in 2002 and received his first commission from a local entrepreneur who had made his fortune doing business with China.

“He asked for something unique,” says Mamani, showing me an image of a bright green building, part Space Invader, part ancient temple. “So that’s what he got.”

It was the first of what was to become his trademark typology: a mixed-use funhouse, with commercial space on the ground floor, a double-height party hall above, and a couple of floors of rental apartments, all topped with a house for the owner on the roof, set back on its own terrace. Others spotted it, and soon he was inundated with clients, each demanding a party palace wilder and more ornate than the next. They are big investments – his buildings cost between $200,000–$500,000 to build – but his clients make the money back in a couple of years from renting out their elaborate event halls in a culture that seems to move from one festivity to the next.

“El Alto is famous for its parties and folk festivals, for which people really dress up,” Mamani says, adding that the women’s embroidered pollera skirts and jewellery can cost up to $10,000. “I thought it would be nice to have an equally impressive indoor space for these parties.”

His “salones de eventos” are funfair fantasies, supercharged stage sets for weddings, birthday parties and other beer-soaked revelries. Striped columns rise to ceilings that heave with plaster mouldings, adorned with plump chandeliers and strips of LED lighting, while mirror-panelled mezzanines reflect the swirling prismatic dream into infinity. They have the air of a Macau casino, except everything is handmade from polystyrene and plaster, sculpted with homemade tools, to designs that Mamani sketches freehand on the walls, with most details worked out on the spot. Seeing his work in the flesh in Paris, it has a handcrafted subtlety that photographs don’t convey, with paint finishes especially textured to mimic the different kinds of rough and smooth weaves of the region’s traditional textiles.

Back in El Alto, his facades take on ever more elaborate iconography, no two the same. One takes the abstracted form of a vicuña, a kind of wild llama, its L-shaped body rising to a pointed ear-like peak on the roof. Another has the scaly form of a viper winding its way around the windows, culminating with the head of a condor, both symbols found in the ancient ruins of Tiwanaku. “One client asked me to incorporate a toad, a skeleton and a sword,” says Mamani. “It was too much, but I did put a big red lance in the middle of the facade.”

This heady fusion of ancient symbolism and pop sci-fi is a fitting architectural language for the new bourgeoisie of El Alto, a city that has grown as a bubbling melting pot of tradition and modernity. Beginning as a suburb of La Paz, it became a gateway for rural migrants coming to the city, a meeting place of miners, farmers and young entrepreneurs prospering from trade connections with east Asia. Thanks to its location at the crossroads of routes linking La Paz to the rest of the country, it operates as a kind of dry port, seeing huge quantities of Asian merchandise arriving from Peru and Chile, to be distributed across Bolivia and beyond.

It has created a newly minted merchant class whose aspirations are perfectly embodied in the chalets – or “cholets” – that perch atop Mamani’s buildings, striking duplex structures that enjoy light, views and private roof terraces, poking up above the low-rise skyline. The name began as an insult, a cross between “cholo” (a derogatory word for a rural migrant) and chalet, but Mamani decided to embrace it.

In a revealing documentary about his work, titled Cholet, a range of distinguished Bolivian architects and academics queue up to dismiss his buildings as “mere facadism”, claiming it is “not architecture, just decoration”. Sick of the criticism that he’s not a real architect, he decided to study architecture, finally receiving his diploma last month. “My critics made me an architect,” he grins.

His practice (which consists of his six siblings) is now completing work on a 12-storey hotel, the first of its kind in the city, and Mamani has even designed a new police station for El Alto, currently awaiting funding. It has eschewed the lurid clothing for a more sober palette of grey and blue, but the jazzy geometric motifs remain.

The po-faced academy may refuse to accept his work, no doubt jealous of the international attention this humble cholo is receiving, but if imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Mamani has reason to be pleased: there are copies of his buildings cropping up all across town. He is happy that his “neo-Andean” style has taken root, and he hopes to move into making more public buildings. Seeing a need for a shift in architectural culture towards the popular, he even plans to start his own architecture school. “We need to start the change in our colleges,” he says. “Architects must get closer to their clients, to our society, to the people.”

- Southern Geometries, from Mexico to Patagonia is at the Cartier Foundation, Paris, until 24 February.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.