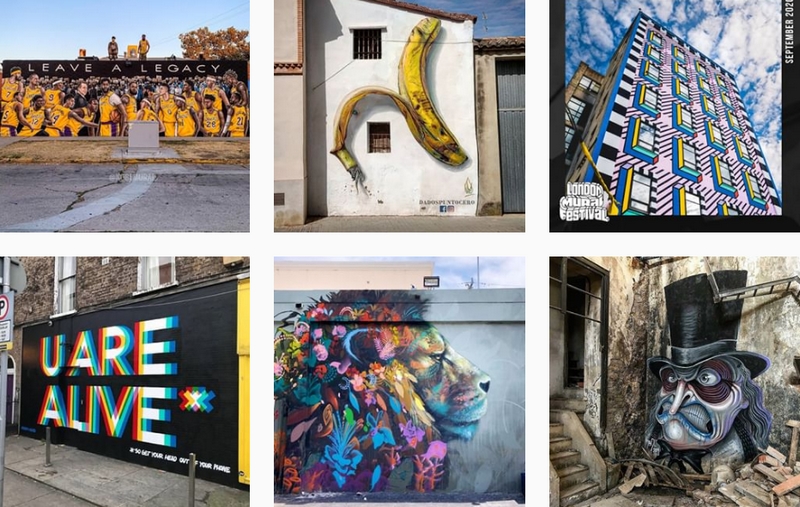

The first-ever London Mural Festival will take place throughout September 2020.

photos @instagram.com/globalstreetart/; @londonmuralfestival.com

The festival sets out to use London as a vast canvas, painting a minimum of 20+ new large-scale murals across the city.

“Culture and the arts are synonymous with London and it’s the number one reason that visitors come here. The London Mural Festival is a fantastic innovative addition to our cultural landscape and really puts London in the spotlight as a dynamic and creative city.” – Laura Citron, CEO of London & Partners.

It has gone from a nuisance sub-culture to a mainstream art form. Now more than 100 street artists and muralists will descend on London for the inaugural London Mural Festival (LMF), which promises to offer accessible art at a time of social distancing.

Artists will create murals at more than 50 locations across the capital during next month’s festival which, its organisers say, will allow people to admire art while restrictions are making gallery visiting difficult.

The festival is the latest step in the transformation of street art, and follows Banksy’s move to join “blue chip” artists such as Keith Haring, after his work Devolved Parliament sold for almost £10m at Sotheby’s in November.

Lee Bofkin, CEO and co-founder of Global Street Art, the organisation behind the LMF, says that unlike major art fairs or exhibitions, which have been cancelled or were operating at reduced capacity because of social distancing, street art was “a non-contact sport” created and viewed outdoors. “You’ve got people up in lifts painting, so they’re not close to members of the public. It’s the kind of thing that you can do at social distance,” he says.

The festival will take place across the capital at more than 50 sites, including Wembley Park, King’s Cross, Holborn, Crystal Palace, Canary Wharf, the City, Camden, Hackney Wick and Tottenham. It will also feature a restored mural painted in Whitfield Gardens in Fitzrovia by Mick Jones and Simon Barber in 1980.

LMF has worked with councils, residents’ associations, private landlords and commercial partners, including Lend Lease and Quintain, to locate available spaces – not easy in a city where paintable locations are hard to find, Bofkin says.

“One of the biggest challenges of a mural festival, and why we think that there hasn’t been a London mural festival before, is because there aren’t the big walls that you might have in an industrial district in Miami or a giant wall that you might find on a Polish tower block built in the 1960s,” he says.

Street art and murals have had an effect on the communities where they are found. In 2016, Warwick University researchers found the London postcodes with street art experienced vast rises in house prices, while in New York the estimated value of a building that had a mural by the Brazilian street artist Eduardo Kobra, increased by about 135% in less than five years.

While that brings benefits, it has indirect costs, say critics, who believe developers use street art to inflate prices and that it can exacerbate gentrification.

Bofkin says there are “complicated issues” around murals and housing but that Global Street Art’s work had helped to reduce the cost of graffiti cleanup for local councils and housing associations, as murals replaced tagging. “Public art is good for creating interest and regenerating spaces, but there is that tension,” says Bofkin. “That’s why we’ve got such a breadth of spaces that we’re trying to paint, including the housing estates.”

Camille Walala, who is creating two works as part of LMF, one at Rich Mix in east London and another that will wrap around Canary Wharf’s Adams Plaza Bridge, says the art form was popular because of its accessibility.

“When I started around 15 years ago I found the street art was quite dark,” she says. “But what I love about Keith Haring is he just wanted … to give something to people who might not be able to go to museum.”

The role of murals has become a major talking point in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. The New Yorker said the “pavement itself has become part of the protest” after the commissioning of several murals in support of the movement in the US sparked criticism from Donald Trump, who called BLM a “hate group”.

“If someone’s got something to say that’s political, and it makes sense, then murals and muralism have a part in expressing that,” says Bofkin. “Sometimes you can say something political, you can make a statement and then other times you can just have fun.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.