If you walk into the Met Fifth Avenue, there is one unlikely sign gracing the entranceway of an exhibit, which reads: “The Metropolitan Museum of Art is situated on the Lenape island of Manhahtaan (Mannahatta) in Lenapehoking, the Lenape homeland.”

It continues: “We pay respect to the Lenape peoples – past, present, and future – and their continuing presence in the homeland and throughout the Lenape diaspora.”

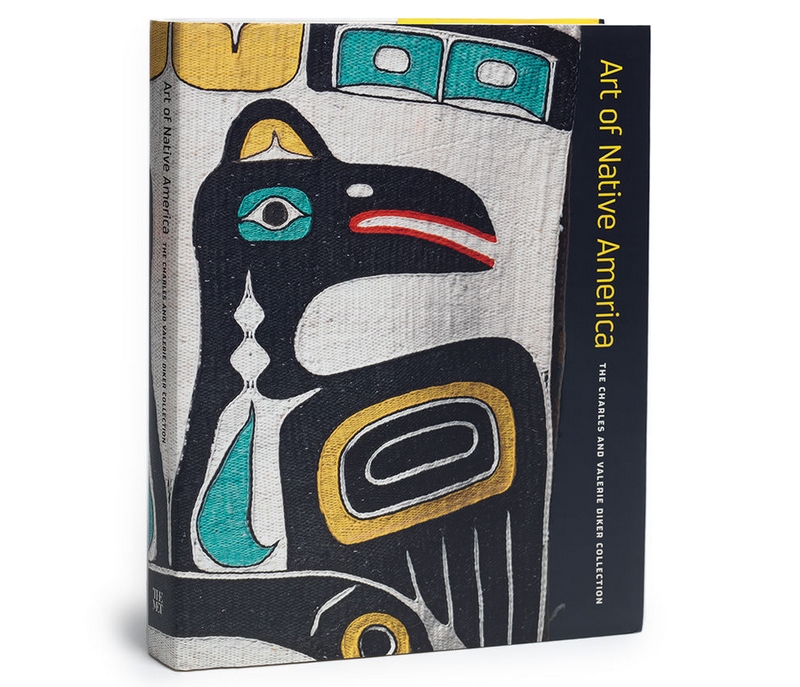

This is not your typical museum wall label, but it’s fitting for the exhibition Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, which runs until next fall and features 116 artworks from over 50 different Native tribes, ranging from pottery to drawings, rare objects from the eastern Woodlands to handmade baskets. A concurring exhibit, Artistic Encounters with Indigenous America, will open at the Met Fifth Avenue on 3 December.

“We felt it was critical to add the land acknowledgement – as well as the longer welcome with the Native-language greeting –— in order to honor the original inhabitants of the land on which the Met sits,” said Sylvia Yount, curator of the American wing, “which is a first for us.”

The Met invited representatives of the Lenape Center of New York to deliver a public blessing at the opening reception, and the exhibit includes a series of talks and presentations with local tribal communities and Native artists.

“What does it really mean to call yourself ‘an encyclopedic institution’, if you’re not really telling and sharing all these different stories?” asks Yount. “But even opening up the door a little bit, which is what we are doing now in the American wing, I think it really does encourage people to think about this work in really different ways, and to think about your own history, your own nationalism.”

The fact that this exhibit is in the American wing – and not in Art from Africa, Oceania and the Americas, signals a change to the curator. “It allows us to tell the story of American culture, history and identity,” said Yount. “What does it mean to bring indigenous art into predominantly a wing of Euro-American production? That’s how it’s always been since 1924.”

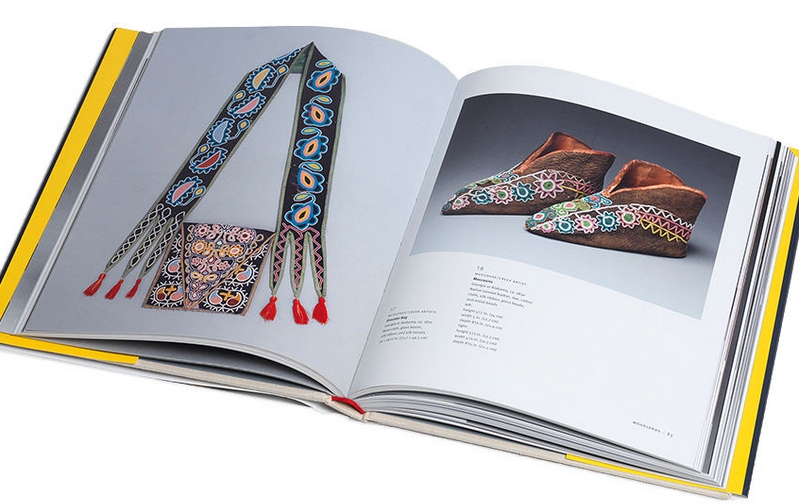

The exhibit features artwork made by Native artists, including one piece by Standing Bear entitled Battle of Little Bighorn, showing the 1876 battle between the US army and Indigenous armies. There is also a shaman’s amulet from Alaska, masks from the northwest coast, clothing from the arctic and moccasins from Alabama.

“These aren’t extinct cultures, many cultures are still continuing, like with traditional beadwork and basket-making,” said Yount. “We are doing programming with contemporary artists and tribal leaders to make sure dialogues are visible.”

It’s a timely show given that Native Americans are still working to counter racist stereotypes, maintain their land and even keep their vote. “It’s a critical moment culturally where everything is so fraught,” said Yount. “It’s particularly relevant now as we think about ideas of America, and who gets to call themselves American, is one of the underlining subtexts of this.”

The second exhibition opening at the Met Fifth Avenue on 3 December, Artistic Encounters with Indigenous America, shows how Native artists have been presented in American and European art, from Indian princesses to warriors and genocide.

The exhibit is loaded with misconceptions, like in The Discovery of America, a painting of a nude woman by Dutch artist Jan van der Straet from the 16th century.

“It shows how ‘America’ is personified as an Indigenous person – in this case, a Native woman wearing only a feather cap, belt and jeweled anklets,” said the curator, Shannon Vittoria. “Like many European artists of the 16th century, the artist didn’t travel to the Americas, but instead invented visual conventions to depict Indigenous peoples that he knew little about.”

By showing past mistakes, it hopes to counter that. “It offers an opportunity to better understand the origins of these long-lasting stereotypes,” she adds, “many of which unfortunately continue today.”

The exhibit includes Osage warriors painted by French artist Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, landscapes by German artist Emanuel Leutze and portraits by American sculptor Henry Kirke Brown. There are portraits of Ojibwe tribal leaders like Reverend Peter Jones, taken by Scottish photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, and a photo of Chief Joseph by American photographer Charles Milton Bell.

“Although these portraits of tribal leaders were often intended to serve a documentary purpose, the sitters were not merely passive participants, they used their agency to express their individuality in these images,” said Vittoria. “They often reveal their resistance to the US government’s policies of cultural destruction and forced assimilation.”

Though most of the Native Americans here are viewed through the lens of European and American artists, self-representation is still included. There are Plains Indian narrative drawings, detailing massacres, battles, hunting and religious practices in paintings on fabric from the late 19th century, alongside contemporary art by Wendy Red Star, who gives a pop art spin to traditional Native American clichés.

And even today, the misconceptions and stereotypes around Native Americans are still present, from pop culture to cartoons and advertisements.

“These images were produced amid colonization, genocide, dispossession and cultural destruction,” said Vittoria. “In the end, they reveal very little about the realities of Native life, but instead reflect the attitudes and anxieties of the artists and societies that produced them.”

- Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection will run until 6 October 2019

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.