It all began in 1966 in a scruffy shop in Greek Street, Soho. Thea Porter, who was born in 1927 and spent her early life in Syria and Lebanon, started off selling furniture and textiles: “huge embroidered Indian bedspreads, pieces of pearl-encrusted Ottoman furniture, wall hangings to cover the damp patches”. She was swiftly adopted by “rich hippies, actors, musicians and their women” who wanted her to make them clothes and went on to design for the Beatles, Mick Jagger and Diana Ross. She became queen of bohemian chic. In the last week of his life, Jimi Hendrix asked Porter to make him a black-and-white peacock-printed shirt. He showed up at her shop with “armfuls of carnations, so many that we couldn’t find vases for them”. He picked up empty milk bottles and a Coke can from the street and arranged his flowers in them. That was Hendrix’s homage to Porter. This captivating book is her daughter, Venetia’s. The text is Thea Porter’s own – written, after her business ended in 1986, at the prompting of her brother, Patrick Seale, a literary agent (and, for many years, the Observer’s Middle East correspondent).

In the Damascus of the 1930s, the young Porter made shifts out of walnut leaves (“I can still recall the bitter smell… until they withered and fell off”). Her father was a Jew turned Presbyterian missionary (more engaged with social and educational work than with the conversion of souls). Her mother was French and a midwife, with a taste for the exotic: “Damascus soaps, brocade, silver-threaded silks, French bottles of scent and stockings.”

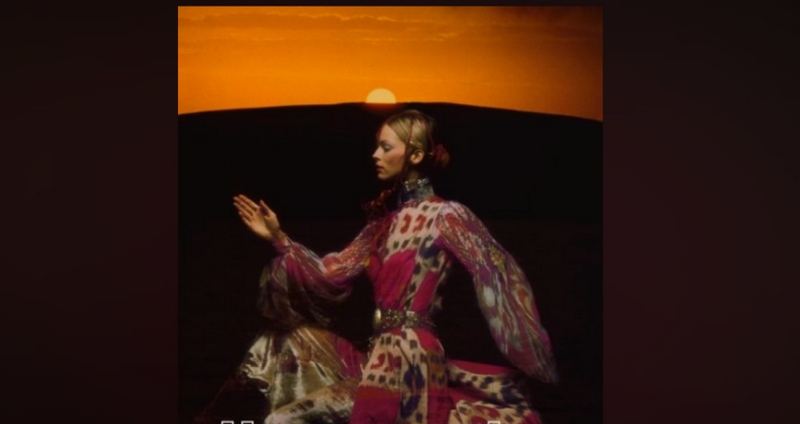

Porter’s writing resembles her designs – it is often, as this list suggests, a sensual patchwork. She revels in everything from Syrian ice cream thickly topped with pistachio to gold bangles and precious stones. Like a wardrobe overflowing with wondrous clothes, the book is stuffed with photographs and paintings. She was a considerable artist too.

Porter had stores in London, Paris and New York and worked tirelessly, policing every sequin. Youthful wrangling with Beirut’s “bullying dressmakers” helped her, she claimed, in London. The Observer journalist Katharine Whitehorn declared she had “as much leisure and luxury as an 18th-century ladies’ maid”, and it was her hard work that led to the appearance of a sublime effortlessness. In a 1971 black-and-white photograph from the New York Times Magazine, a piratical man lounges, his billowing sleeves patterned in scales as if he were part merman, white ruffles lapping on his chest. Above him are two sultry, windblown women, one in diaphanous fabric, the other with wide sleeves twice trimmed in velvet. Are they his sirens or he their plaything? Porter understood sexiness, commenting: “A body with clothes on is more erotic than a body that is nude.” A cover from a 70s National Enquirer shows Elizabeth Taylor smouldering, cigarette in hand. Her mouth is slightly open, Porter’s gold brocade seethes on her bosom. The caption reads: “What do you expect me to do? Sleep alone?” An interview with Barry Humphries reveals that when Edna Everage’s taste took a turn for the better, Porter made “her” frocks.

Venetia Porter, in her moving introduction, touches on the sadness of her mother’s last years (she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 1994). She describes bringing Thea scraps of velvet and her favourite scent, Tabac Blond, by Caron, to soothe and revive. She recalls a tragicomic trip to Marks and Spencer, where the front entrance caused such distress, they turned back “shaking and empty-handed”. In old age, Porter carried a handbag with a wooden handle in which she kept refinding Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu.

She died in 2000 but her clothes are still adored by their owners (in a 2015 photo, Kate Moss, in black, gold and orange, looks like a startling Gypsy). Like Virginia Woolf, who once described women as “now dull and fat as bacon, now transparent as a hanging glass”, Porter understood the changeability of women’s beauty. She thought a dress should flatter, never upstage its owner. Her sympathetic belief was that women should refuse to be “cowed” by fashion and “think only of what suits them”.

• Thea Porter’s Scrapbook, edited by Venetia Porter, is published by Unicorn (£30). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.