“Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up” exhibition at V&A museum is a fresh perspective on Kahlo’s compelling life story through her most intimate personal belongings. This exhibition presents an extraordinary collection of personal artefacts and clothing belonging to the iconic Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. Locked away for 50 years after her death, this collection has never before been exhibited outside Mexico.

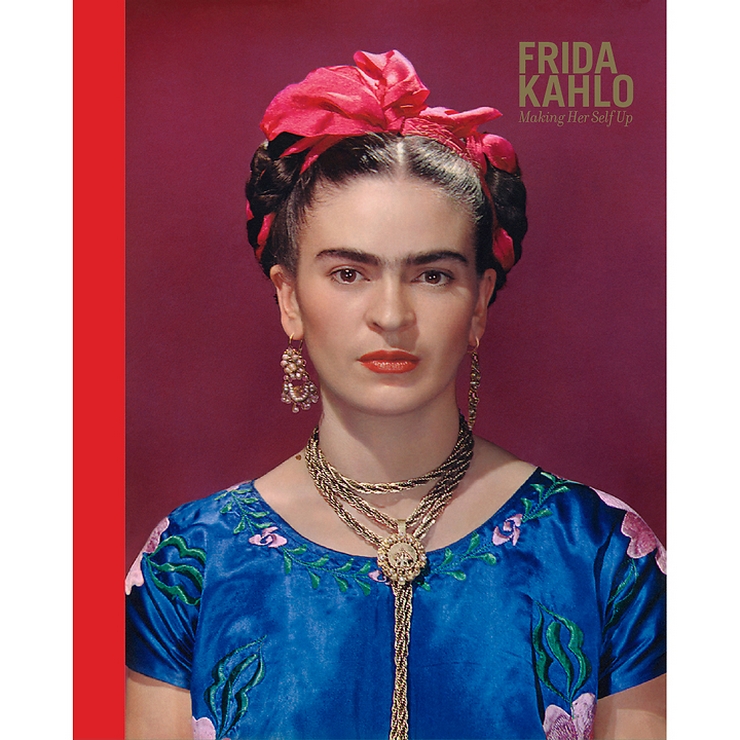

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up book: photo: vam.ac.uk/shop/

This feels wrong. I am looking at Frida Kahlo’s prosthetic leg. There is a glamorous red boot on it. The matching boot is also in the display case, yet the woman who wore the leg and boots is long gone. She died in 1954, when she was 47. Would she want her artificial limb to outlive her like this?

It’s true, she wore it bravely. Everything about Kahlo was courageous. She was a revolutionary, a passionate lover, a bold artist. As a child she survived polio, then in 1925, when she was 18, she was in a bus crash that left her with lifelong disability and pain. At the heart of the V&A’s highly unusual and problematic retrospective is a shrine to that pain. There are corsets and body casts on which she painted the communist hammer and sickle; medicines and painkillers, crutches and built-up shoes. However, there are simply not enough of her compelling works of art.

Kahlo was, as this exhibition reveals with sensationalist clarity, someone who suffered. Yet she was also someone who created. She did not endure her life. She transfigured it, into blazing, visionary paintings. These take a back seat at the V&A to Kahlo’s clothes, makeup and iconic image. I suppose this is what artistic fame looks like in 2018.

In her lifetime, Kahlo was much less renowned than her unfaithful husband Diego Rivera, who had known Picasso in Paris before returning to Mexico to create revolutionary murals. Today he is a lot less reverenced than her. (Even Jeremy Corbyn misspells the name of this once-lauded radical painter, calling him “Diego Viera”.) Yet it seems that in becoming globally popular, Kahlo has become an image, not an artist. Her creativity is treated here as almost incidental to her charismatic personality.

Is that how it was always bound to end up? In the 80s, Kahlo’s paintings were rediscovered by feminists and collected by Madonna. Then, with weary sniffs, along came the art critics. Ask one of these characters, especially a male one, and he will mutter into his cravat that Kahlo’s paintings are really not very good at all. Crude, simplistic self-portraits. Were those critics right? Is it the biography that matters, after all? Or, to put it more fashionably and cleverly, was Kahlo’s life her real art all along?

For this exhibition reinvents Kahlo as a 21st-century artist whose life was a kind of performance, whose self-fashioning was an act of creation and whose pill bottles are as significant as her drawings. When a sealed room in her house in Mexico City was opened in 2004 to reveal a treasure trove of her private belongings, from unseen photographs to well-preserved shawls and skirts, it was as if she’d been given a millennial makeover. An entirely new way of seeing her was revealed – and the curators of this show jump on it to discover a Frida who was the Grayson Perry of her day, inventing herself in an array of spectacular costumes. Her shawl gets a wall display to itself, her silver jewellery elicits gasps.

Yet Kahlo did not see her art that way. Her work, for her, was what she made with pencil and brush. It was extremely close to her life, rooted in her life – but made magical by imagination. It becomes clear that this show has misread the connection between art and reality when it recreates one of her most powerful self-portraits as a fashion tableau.

In 1939, Kahlo painted The Two Fridas, herself and her double, holding hands, with exposed hearts connected by a shared artery: one of the Fridas has cut the artery, spilling crimson blood on her white skirt. In this show two mannequins re-enact the scene dressed in Kahlo’s clothes. Yet this recreation is decorous and emotionless. There are no exposed hearts. There’s no blood on the immaculately conserved clothes.

I simply disagree with the curators’ interpretation of Kahlo. She wouldn’t want us to be gawping at her possessions, however arresting they might be. She’d want us to be encountering her art – and it is well worth encountering. When we do get to see it, the emotional revelation is on a different level. In her 1943 Self Portrait as a Tehuana, she wears a fantastical white headdress that surrounds her face as if she was the red centre of a radiating flower. Dark tendrils or hairs radiate like a spider web over the pearly satin. On her forehead is a miniature portrait of Rivera, the disloyal lover who is, literally, always on her mind.

Nearby is the actual costume in the painting, or one very like it. This is a beautiful, spooky moment as the stuff of Kahlo’s life is displayed next to the art she made from it. Yet the painting is alive in a way the old clothes are not. Looking into the image that Kahlo painted of herself is like gazing into her soul, her being. When she translated her life into art she expressed something inward, mysterious. It’s fascinating to compare her few self-portraits in the exhibition with the many photographs of her on view. Kahlo, you realise, made herself less beautiful in her paintings than she was. She painted an inner self, not her exterior appearance. Her depictions of her accident and its lifelong consequences are equally metamorphosed in her painted and crayoned diary. She is a magic realist, portraying herself with a broken classical column for a spine in a surrealist art of decay and dissolution.

Some of that is here, but not enough. Original drawings are fleshed out by facsimiles. There’s a facsimile of the diary, too. All the makeup is real, though. Tantalising glimpses of her artistic brilliance are overshadowed by her relics. She has passed into populist sainthood.

It is like visiting an exhibition of a dead Aztec queen’s tomb treasures. This is an archaeological exhibit, not an artistic one. As such it is awe-inspiring – but is it truly “intimate”, as it is billed? I feel a far greater intimacy looking into Kahlo’s eyes in her paintings than I do wandering among 80-year-old clothes. Artists live on in their art. This exhibition overwhelms Kahlo’s living legacy with its excessive adoration of a dead woman’s stuff.

• Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up is at the V&A, London from 16 June to 4 November.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.