She offers herself up to the painter, lying back on a rich red bed, her eyes as black as desire. This is not an academic study of the nude; this is a painting about sex.

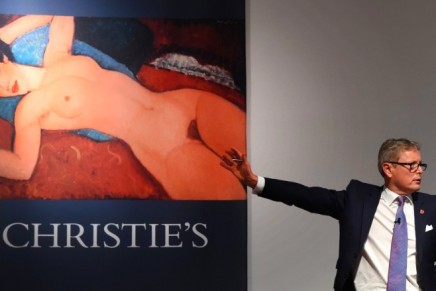

Amedeo Modigliani was high on hashish, wrecked by absinthe, and desperately poor when he painted this hymn to lust in 1917-18. Almost a century later, Nu couché is the second most expensive painting ever sold. On Monday night it went for $170.4m (£113m) at Christie’s in New York. Only Picasso, whose Women of Algiers set the $179m record for a painting sold at auction in May, is more expensive.

You can picture their ghosts meeting in some forgotten Paris cafe, wryly considering those numbers, and remembering the outsiderdom and bohemian raggedness out of which their art was born. Picasso’s friend André Salmon said that even by the standards of the avant garde, Modigliani was maudit – “cursed”. By 1920 he would be dead of tuberculosis, exacerbated by drugs and drink. Now his reclining nude is lighting up the news with a flash of high culture erotica and financial pornography. Cursed in life, Modigliani has been blessed by the market.

One thing this proves is that art collectors bidding at auction, with millions at their disposal, are no different from you or I going into a bookshop and coming out with Fifty Shades of Grey, or perhaps something more Parisian like The Story of O. Sex is the greatest salesman of all. Even more graphically than Picasso’s Women of Algiers with their multiple breasts and bums, Nu couché is a sensual masterpiece – and far more conventionally so than anything Picasso painted.

Modigliani was always destined to be a collector’s favourite because he mixes modernist thrills with traditional seduction. You could almost call this a cynical market-minded cocktail, if the hard fire of Nu couché were not so ecstatic and obsessive. Modigliani never forgot his heritage as an Italian artist – a Tuscan one at that, who grew up with more access to Titian and Botticelli than to French modernism. It is one of no less than 26 reclining nudes by him and they can all be traced back to Titian’s Venus of Urbino, the greatest Renaissance nude, which he would have seen in the Uffizi gallery in Florence.

That centuries-old Italian tradition of glorifying the human body infuses the sexuality of Nu couché, yet Modigliani sees beauty with eyes reawakened through the explosions of modern art. Picasso and Matisse reinvented the human body a decade before he painted Nu couché. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and other “primitivist” works he did in 1906 and 1907 give Modigliani’s woman her mask-like gaze and geometrical frankness, Matisse’s 1907 Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra) her flamboyant display and raunchy hips.

Ten years after this revolution, the world had become a darker place. Modigliani was too ill to serve in the first world war, and his art is a reminder not to assume it affected every artist in the same way. One response to this massacre of youth was Dada, which expressed the despair of a doomed generation in brutal collages. Another was to escape into a world of desperate hedonism. Modigliani and his lover Jeanne Hébuterne lived this way in Paris, just as the equally sex-obsessed Egon Schiele was drawing inflammatory nudes in Austria. Both died soon after the war their ill health kept them out of. Both left a truly modernist message that art and life are the same thing – and that the big world of war and history is alien to both.

It would be easy to accuse the art market of a covert conservatism in falling for Modigliani’s nude. Shouldn’t the anonymous Chinese buyer be forking out for some truly “radical” work like Duchamp’s urinal (which also dates from 1917)? But it is an adolescent travesty of the story of modern art to see it as one succession of fragmentations, destructions and rejections. The first modern artists had an immense appetite for visual luxury. No paintings have ever been easier on the eye than the great modernist nudes. The art market has got it right, if you can stomach all those zeros. This is one of the great modern paintings and it is worth any sum you like.

Modigliani painted Nu couché in a world at war – a world of propaganda, guns and mass slaughter. Through an absinthe haze, he insists that he is not part of the massacre, not party to the hate. What he sees is his lover in her majesty, become Venus or some Tahitian fantasy. Her eyes are portals of forgetting. Modigliani is a religious artist and his religion is desire. This is a beautiful act of defiance.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.