Globally, nearly three-fifths of clothing ends up in an incinerator or landfill site within a year of being made. Shopping for clothes is no longer a harmless pastime; it is yet another painful frontier between desire and conscience. No wonder so-called “sustainable fashion” is popping up on retail sites from Boohoo to Bloomingdale’s. But Orsola de Castro, co-founder of Fashion Revolution – a nonprofit movement campaigning for a more socially and environmentally responsible fashion industry – dislikes that term. “I just call it good design looking for solutions,” she says. But, whatever you call it, this approach is booming: the fashion search site Lyst recorded a 47% increase in shoppers looking for items through terms including “organic cotton” and “vegan leather” last year, while searches for the sustainable shoe brand Veja were up 113%. From upcyclers to zero wasters, activists to fabric inventors, here are six young labels that offer great design for the thoughtfully stylish – and might just change the way the wider industry thinks about fashion.

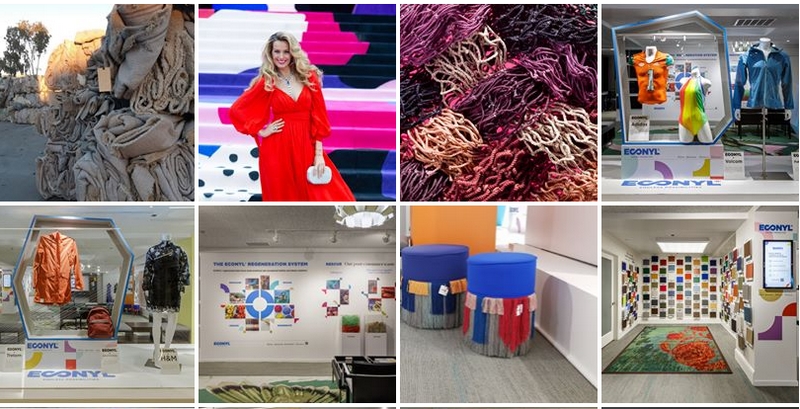

Econyl – the brand turning old fishing nets into swimwear that can be endlessly recycled

Swimwear brands that use postconsumer recycled fabric are garnering a lot of attention. Auria London has dressed Daisy Lowe and Rihanna. Davy J has swimsuits for wild and sporting swimmers. Ruby Moon offers “activewear for activists”. Fisch is stocked at Matches. Mara Hoffman’s pieces sell for hundreds of pounds. But follow the stories of all these labels and you will arrive in the same place: at Econyl, a recycled nylon fibre that its Italian manufacturer claims is “infinitely recyclable”.

“At the beginning, many people were laughing at me,” says Giulio Bonazzi, CEO of Econyl’s parent company, Aquafil. An average of 64,000 tonnes of fishing nets are left in the ocean each year, and these were the first nylon items that Bonazzi’s company collected for recycling, initially from the fish farming industry in Scotland and Norway, from professional divers who spotted ghost nets, and now from “all over the world – Japan, Australia, south-east Asia, north and South America”.

Lejeune says that, when she started the Ethical Fashion Forum in 2006, plastic as an issue was not on her radar. “That has really changed in the past two years.” There is an obvious and pleasing circularity to the idea of swimmers bathing in recycled ocean waste. No wonder small fashion brands are not the only ones to love Econyl. Gucci adopted the fibre in 2017. Stella McCartney has pledged to stop using virgin nylon by 2020, switching to Econyl (she makes bags with it, too.)

The company now has more than 750 fashion clients and “demand is growing strongly day by day”, Bonazzi says. He has his sights set on the plastic industry at large – “glasses, furniture, chairs”, he rattles off – and even nets in which to transport and sell supermarket fruit.

Ninety Percent – the brand giving away its profits

“We are trying a crazy idea and seeing if it connects with people,” says Shafiq Hassan, co-founder of Ninety Percent, which sells well-cut organic cotton T-shirts, tie-dye hoodie dresses, asymmetric skirts and leisurewear. The brand gives away 90% of distributed profits, putting philanthropy centre stage. The people who make its clothes, in Bangladesh and Turkey, get 5%, the people who build the brand get 5%, and the rest is split between four charities, which consumers help to choose. Each piece’s care label carries a code that shoppers type into the website to vote for their preferred beneficiary.

As Tamsin Lejeune, founder of the Ethical Fashion Forum and CEO of the new enterprise Common Objective, points out, Ninety Percent is interesting because “some of the best and most innovative examples of change in the fashion industry are coming from the supply sector”. As for Hassan, his family moved from Bangladesh to England in 1971; and he lived his teenage years listening to John Lennon’s Imagine and Pink Floyd’s Breathe (“Don’t be afraid to care …”).

On a sourcing trip for New Look in the early 90s, he drove past the dump near Kamalapur railway station in Bangladesh. The smell was appalling, but worse still he could see “children eking out a living there”, and started to think about a sustainable business model. With his partner Para Hamilton, he set up the charity Children’s Hope (one of Ninety Percent’s beneficiaries). When the pair opened a factory in 2009, they provided a canteen with fresh food cooked daily. Other benefits include health insurance and on-site healthcare (there are now 12,000 employees and the factory has produced clothes for H&M, Debenhams and New Look.)

“Younger companies have to lead the way in sustainability,” Hassan says. But while Ninety Percent sounds like a radical idea, it is the result of decades of experience in the Bangladesh garment industry. Some of Hassan’s questions remain. “How can we be an agent of change? How can we share empathy, compassion, value, purpose and transparency? Power to the people, [that] sort of thing.”

Matthew Needham – transforming shopping trolleys into raincoats

Matthew Needham was an intern at a major luxury brand in Paris where he saw firsthand the degree to which waste is built into the fashion industry. “It takes 10 weeks to order leather from the tannery, so the brands tend to order more colours than they need,” he says. They decide only when they arrive which to use and which to dispose of. “For me, the waste was thoughtless”. He describes himself as an upcycler, an approach shared by fellow designers Bethany Williams, who has worked with materials including book waste, and Helen Kirkum, with her amazing mash-up trainers made from discarded shoes.

Needham, like De Castro, believes that sustainability “should be inherent in the design process for everyone”. He finds luxury deadstock before it goes to incineration (“Like the Burberry thing” – where the company destroyed £28m of its own products to guard against counterfeiting). He scours markets, the streets and sometimes his own studio. After a shopping trolley with no apparent owner sat in the street for two weeks, he turned it into a raincoat. Lace-like plastic found on a beach in Norway became a skirt. Often he blends these finds with high-end unused fabric, such as tweed that might have been Chanel, but instead spent years in a warehouse. “I like the idea of considering the value in creativity. Not the value in the materialistic thing itself, but the value in the creativity. That’s luxury. The craft, the skill, the mindset, the thought process that goes into making something,” he says.

His work has already appeared in i-D and he is often approached by big-name brands wanting to benefit by association. He usually declines. “For them, I’m a tick box.” Needham creates pieces to order; a deal with a major retailer is only a matter of time away. Being at the start of his career, he says, is a major advantage. “You have the benefit of not being tied down by marketing and business plans. You really have to decide for yourself what you think sustainable is. For me, it’s about using what we have, because we have too much.”

Kayu – the brand turning straw into sustainable fashion gold

Jamie Lim grew up in Malaysia and Hong Kong. She loved the batik prints her parents wore, the beautiful furniture made of straw. At 17 she moved to the US for university, and each time she went home on vacation she looked for artisanal gifts to take back for friends. As time went by, they became harder to find. Plastic straw began to proliferate. “So that was the impetus of the brand – it started as a way to preserve indigenous techniques,” Lim says.

Now, Kayu’s beautiful bags – California-style totes handwoven from natural plant fibres by artisans in Terengganu, Malaysia – are stocked at high-end stores including Liberty, Bloomingdale’s, Saks Fifth Avenue and Net-a-Porter. Reese Witherspoon and Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, carry them.

Crucially, these bags look great. They prove that conscientious fashion can compete with, and lead, the mainstream fashion industry in terms of aesthetics and design. “What they are producing is absolutely beautiful, and completely separate from what you might think of as sustainable fashion,” says Emma Slade Edmondson, a creative consultant who specialises in sustainability and ethics in fashion retail.

Lim is also in the process of steering Kayu towards zero waste. Excess fibre from the bags is being made into alphabet tags or pouches, with the proceeds donated to charity. The straw waste is biodegradable, of course, as are the bags, over time, although some of the hardware is not.

“At the beginning, people weren’t really on board. Now our customers are asking lots of questions. Is the straw plastic or real? Is it vegan? Have the bags been mass-produced?” And retailers are also asking those questions, Lim says. “Net-a-Porter asks the designers, what are your sustainable initiatives? [And] consumers really demand it.”

Mud Jeans – creating a rental revolution in denim

“The idea was to make jeans – organic cotton, people getting properly paid,” says Bert van Son, who founded Mud in 2012. Nothing too radical there. “But we soon found out that cotton could be easily recycled. We thought: why not get the jeans back?” Mud offers a choice between buying jeans or leasing them. Those who rent simply swap the old ones for new.

“There is a mindshift happening,” Van Son says. “We used to have a 50/50 split between people renting and buying. But over the past 12 months the leasing has grown. People like to take another colour, wash or style after a year. They’re happy to send back their old jeans and get a fresh pair.”

As the rental side of the business grows, so, too, does the proportion of postconsumer recycled waste that the label uses. Initially, Mud jeans blended 20% recycled denim with 80% virgin cotton. Now, the recycled proportion accounts for 40% of each pair. Next year, Van Son is “hoping to announce the first 100% recycled postconsumer pair of jeans”.

The important word in that sentence is “postconsumer”. Other forms of recycling may repurpose offcuts from the factory floor, but postconsumer recycling finds a new life for a garment that might otherwise go to landfill. More than a billion pairs of jeans are sold globally each year, while less than 1% of materials used to produce clothing is recycled into new clothing.

At Mud, the buttons are made of stainless steel, which can be recycled. “The paper tags are cradle-to-cradle certified. We don’t use leather. We are making the pocket linings out of 100% cotton”. And then? “We will try to get biodegradable polyester stitching lining”, says Van Son. “We are purists.”

Birdsong – the brand that brings you face to face with its makers

Anyone buying a piece from Birdsong will come face to face with its maker. The London social enterprise label, which majors on statement tees and classic shifts, puts photographs of the women (they are all women) who cut, sew, embroider or knit the clothes on its labels.

This is not a gimmick. Birdsong’s creators, Sophie Slater and Sarah Neville, started out working in women’s charities. They personally know the 12 to 50 people who make the clothes. “We never set out to make a fashion brand,” Slater says. “We just loved fashion as the conduit, a way to use these women’s skills to bring about change.” Now the clothes are sold in more than 30 countries.

The brand was born out of feminism and the Fashion Revolution movement. Slater and Beckett wanted to take the clothes that were being made in daycare centres and sold in bring-and-buy sales, and showcase them on a stylish website.

“Then we had the idea of collaborating with all these amazing feminist photographers,” Slater says. She enlisted activists she knew how to model the clothes and adopted the slogan: “No sweatshop & no Photoshop.”

Now Birdsong has its own designer, bringing shape and coherence to the talents of the makers. To reduce waste and overstock, the knitwear designer Katie Jones has created a template for crocheted blocks that can be quickly sewn into sweaters or cardigans, depending on orders received.

“Traceability and transparency are big priorities,” says Emma Slade Robinson (she suggests checking out another brand, Know The Origin, too). Slater, for instance, knows the Birdsong makers by name, pays them a London living wage, and has even been to a family wedding. “I guess our mission is to create beautiful things the women enjoy working on, and give them a revenue stream.”

Birdsong’s place in the fashion industry is changing, too. “When we used to be invited to events, it was to give a talk at a hemp convention,” Slater says. But at a recent industry breakfast with representatives from well-known high-street brands, some of Slater’s fellow attendees were discussing whether sustainability was a trend. “I stood up and said, ‘We’ve got 50 harvests left!’” she says – referring to the news that soil fertility will be eroded in the UK in the coming decades. “Me and my friends working in ethical fashion always said we felt like the geeks and the fashion people were the cool ones. Now it feels like they are really paying attention.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.