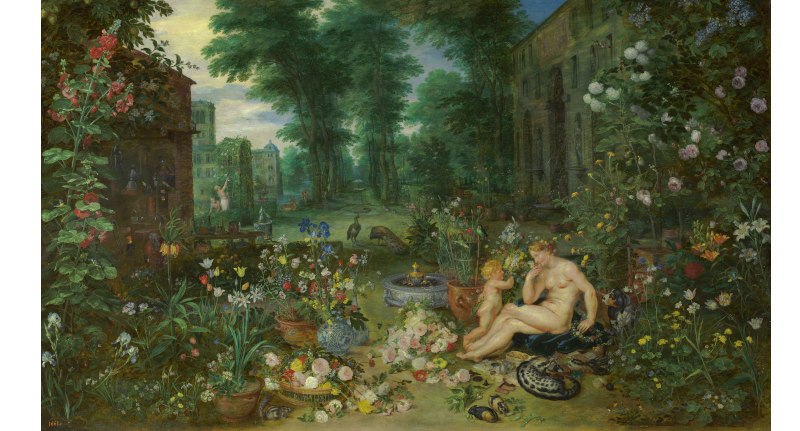

The Sense of Smell by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel The Elder (Oil on panel, 66.5 x 110 cm; 1617 – 1618); Madrid, @Museo Nacional del Prado/ @museodelprado.es

Puig and Prado Museum unveiled a technology unique in the world of perfume. Welcome to The Essence of a Painting. An Olfactory Exhibition

AirParfum technology, installed in Room 83 of the @museoprado in Spain (El Museo del Prado), enables visitors to sample the fragrances that Puig Perfumer @gregorio_sola composed and associated with certain objects in the painting.

For the first time the Prado Museum proposes an olfactory relationship with painting.

“The sense of Smell. An Olfactory Exhibition” proposes a new approach to the Prado collections, this time through the sense of smell. For this purpose, the perfumer Gregorio Sola, with the technological support of Samsung and the special collaboration of the Academia del Perfume and the AirParfum olfactory technology developed by Puig, has created 10 fragrances linked to objects that appear in the work The Smell, part of the set of paintings The Five Senses that Jan Brueghel painted in 1617 and 1618 and in which the allegorical figures are the work of his friend Rubens.

Their sense of smell will enable the visitors to explore the different objects included in this painting. To this end, Gregorio Sola, Senior Perfumer at Puig and Academic of Academia del Perfume, holder of the Sandalwood Chair, has created, for example, Allegory, which invites us to fix our gaze on the bouquet of flowers whose scent the allegorical figure is inhaling; Gloves, which reproduces the scent of a glove perfumed with amber according to a formula dating from 1696; Fig Tree, which prompts us to look for this plant in the picture; Orange Blossom, which focuses our attention on the apparatus used to distil this product; and so on, with a total of 10 fragrances that will accompany the sense of sight to provide a unique experience while viewing the painting.

The Sense of Smell by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel The Elder (Oil on panel, 66.5 x 110 cm; 1617 – 1618); Madrid, @Museo Nacional del Prado/ @museodelprado.es

10 fragrances that can be smelt at the exhibition by means of the AirParfum technology

The AirParfum technology, developed by Puig and unique in the world of perfumery, makes it possible to smell up to 100 different fragrances without saturating the sense of smell, respecting the identity and nuances of each perfume. Thanks to the four diffusers on the Samsung touchscreen monitors installed in the room, visitors will be able to smell the objects from the 17th century portrayed in the painting.

ALLEGORY

This perfume by perfumer Gregorio Sola took its inspiration from the bouquet of flowers whose scent is inhaled by the allegorical figure representing smell, painted by Rubens. It consists of a combination of rose, jasmine and carnation. By general

agreement in the world of perfumery jasmine is considered to be the king of flowers, owing to its strength and luminosity, and rose the queen for its seductiveness and ability to combine with different olfactory families. The spicy facets of carnation contribute volume and sensuality to the bouquet.

PERFUMED GLOVES

In the Modern Age the elites used to perfume their gloves to mask the bad smell of the tanning process and have a pleasant scent around them. Leather gloves from Spain were particularly highly valued at the time. Following a visit to Spain in 1629 Rubens (the painter of the figures in this picture) returned home with a gift of two amber-scented gloves for the Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia, sovereign of the Spanish Netherlands.

The fragrance that can be smelt here reproduces the scent of a glove perfumed with amber according to a formula from 1696, which contained of resins, balsams, woods and flower essences, accompanied by the accord of fine leather.

The Sense of Smell by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel The Elder (Oil on panel, 66.5 x 110 cm; 1617 – 1618); Madrid, @Museo Nacional del Prado/ @museodelprado.es

FIG TREE

This perfume by Gregorio Sola interprets the green and refreshing, humid, vegetal scent of the shade of a fig tree on a summer day. We can perceive the velvety texture of the leaves and the dark colour of the trunk and branches.

Although the fig tree is native to southwest Asia, it has spread naturally around the Mediterranean over the centuries. In the context of the court scene at Brussels evoked by Jan Brueghel’s painting, it is a valuable plant because it is growing outside its usual climatic conditions. It has been planted in a pot so that it can be taken outside on sunny days.

ORANGE BLOSSOM

The essence of neroli is extracted by steam distillation from the flowers of the bitter orange tree. It is what we can smell here. The apparatus on the left side of the picture was used to distil this type of product.

The term “neroli” originated from the aristocrat Marie-Anne de La Trémoille, whose titles included that of Princess of Nerola (in Lazio). In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, she made this fragrance popular by using it to perfume her gloves, clothes and baths.

In northern Europe, where Jan Brueghel worked, the citrus species were highly valued trees grown in greenhouses.

JASMINE

If we immerse jasmine flowers in a volatile liquid with an oily composition, this will be enriched by the flowers’ odoriferous components. When the liquid becomes saturated, it is heated up slightly to provoke evaporation. The resulting wax is called

the “concrete”. This is dissolved in pure alcohol to produce the “absolute”. What we can smell here is a jasmine absolute. It has an intense but delicate scent, with creamy and green facets and a slight animalic note.

Jasmine smells different in the morning than at night, when it is more fragrant. Like some of the other plants seen in the picture, it is an import from warmer climes.

Detail: The Sense of Smell by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel The Elder (Oil on panel, 66.5 x 110 cm; 1617 – 1618); Madrid, @Museo Nacional del Prado/ @museodelprado.es

ROSE

The rose is the most easily recognized of all flowers. Shakespeare wrote in Romeo and Juliet: “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose would smell as sweet by any other name.” According to Pliny the Elder, in the 1st century AD it was already the most commonly used flower for making perfumes.

As described by a perfumer, the scent of the rose is fresh, floral, velvety and intense, with green facets and a slight fruity touch, combined with spicy notes and a subtle honey note.

Three hundred thousand flowers, picked by hand in the early morning, to have a kilo of absolute.

Jan Brueghel painted eight types of rose, including the May and Damask varieties, the most commonly used in perfumery.

IRIS in perfumery

This is probably the most expensive raw material used in perfumery, worth more than twice as much as gold because of the slow, complex production process. The absolute, called “orris”, is not obtained from the flower itself, as in the case of other plants, but from the rhizomes, which have to mature for between five and seven years.

One of the main growing areas is the Tuscany region around Florence and the iris has been the city’s emblem since the Middle Ages. In the first century AD Pliny the Elder wrote that its root was used to obtain ointments and explained that “Iris” was the Ancient Greek word for “rainbow”, hence the name of the flower in view of the wide range of colours found in the species.

DAFFODILS

The narcissus or daffodil used in perfumery is grown mainly in the French region of Aubrac and is harvested in late May and early June. In Jan Brueghel’s time, the essence was obtained by distillation. Nowadays, the method used is solvent extraction, which makes it possible to produce more essential oil. Nonetheless, 1,300 kg of flowers are needed to obtain just one kilo of absolute (one person can collect approximately 105 kg per day).

Its fragrance is very original, strong and heady, with fruity nuances of apricot and peach, combined with almost olive-like notes of leather and a straw-like floral background.

The Sense of Smell by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel The Elder (Oil on panel, 66.5 x 110 cm; 1617 – 1618); Madrid, @Museo Nacional del Prado/ @museodelprado.es

CIVET

This animal has a pouch between its hind legs from which a resinous substance, civet musk, was extracted and used in the past in perfumery. It is a very stable component that was employed as a fixative by binding it to other fragrances to make them last longer on the skin or on an object. It has a strong, animalic smell, almost like excrement. The perfumers of the 17th century masked its unpleasant odour with the essences of flowers, woods, spices and balsams.

Civet was one of the main ingredients with an animal origin used in the perfumes of the time. Today, as in this exhibition, it is produced synthetically.

SPIKENARD

A relief on a façade portrays the anointing of Jesus in Bethany, recounted in the Gospels: “Mary then took a pound of very costly perfume of pure nard, and anointed the feet of Jesus […] and the house was filled with the aroma of the perfume.”

The nard used at that time came from India and was very expensive, while the type used in perfumery when the picture was painted came from Mexico. Today it can cost over €10,000/kg. Due to its strength and intensity, nard essential oil is used to enhance the character of other floral notes in perfumes.