When he was 14, Ljubljana resident Janko Vrhunc spent every Sunday training to drive a steam locomotive. “We had to sign in, then check all the wagons, check the train, then talk to all the workers,” recalls Vrhunc, now 84. “I asked the train driver: is the fire strong enough? I asked the conductor: did we sell enough tickets to depart? Are the uniforms in order?”

After three months Vrhunc and about 20 other schoolchildren were deemed ready to run the small-gauge Pioneer Railway under adult supervision. “We moved the train from Ljubljana main station,” says Vrhunc. “The train driver stepped aside and let us do it. This is how … one of us fell under the wheels and lost a leg.”

When it opened in 1948 it was one of a number of child-run railways built according to communist ideology in Soviet and eastern bloc countries as educational tools to cultivate young people’s interest in technology and prepare them for jobs in engineering. It was a popular novelty at first but when Yugoslavia severed ties with the Soviet Union a few months later, funding and enthusiasm dwindled. In 1954 it was shut down completely.

Today almost no trace of the railway remains in Ljubljana, outside of the memories of the few surviving Pioneers. “There is only a bicycle lane there now,” says Neja Tomšič, project coordinator at the city’s Museum of Transitory Art.

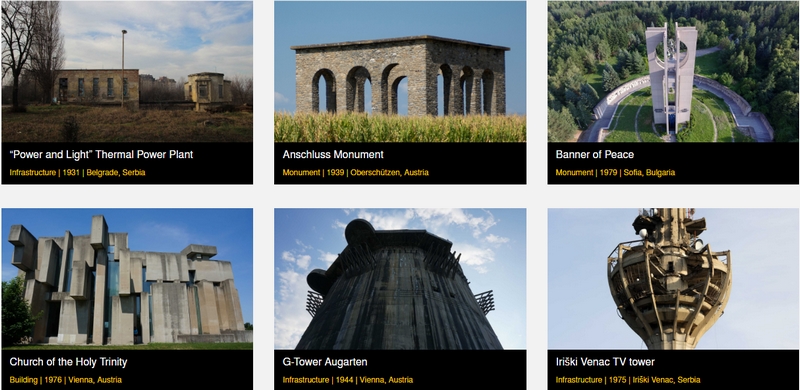

The Pioneer Railway is what she and collaborator Martin Bricelj Baraga term a “nonument” – 20th century architecture, public spaces and infrastructure projects that are abandoned, unwanted or forgotten.

Working with an international team of researchers and artists, Tomšič and Bricelj Baraga study, map and archive fading sites and Brutalist-style structures. They’re building a database of about 120 case studies across Europe and in former Soviet states and will be releasing a book this year.

Tomšič and Bricelj Baraga periodically stage artistic interventions at nonument sites to keep the histories alive. One evening in May, they briefly resurrected Ljubljana’s Pioneer Railway with a light and sound installation. A team of dancers in silver jumpsuits carried glowing tubes along the route as lights in the distance flashed and flared. Playing in the headphones of audience members were audio interviews with several surviving Pioneers like Vrhunc.

“What’s the charm of the railway? The charm is that you didn’t know anything else,” former Pioneer Alojzija Eržen says in one interview. “There was nothing else. You could socialise there. You had so many friends.”

Fani Rižnar, another former Pioneer, now deceased, remembered the railway’s final day. “I stayed until the end, until 10pm, together with the station manager. I cried all the time. I cried until I came home and then also late at night, and I fell asleep crying,” she said. “When they took the railway, they also took a part of me.”

‘People forget what was there’

These nonuments are often in places that have experienced political or social tension, and the buildings or monuments are often polarising. “They’re embodying certain types of conflict that are living in this society still at this time. And I think that’s the reason they’re not preserved,” says Bricelj Baraga.

Many are on the verge of destruction. “As it happens in former Yugoslavia or eastern ex-Socialist countries, they’re just left to rot and decay,” he adds.

Far from eastern Europe, the Nonument Group’s first intervention was actually staged in Baltimore, Maryland. Tomšič had been there in 2014 for an artist residency and became familiar with the large modernist concrete fountain and park space at McKeldin Square.

A multilevel sculpture of plinths and spillovers interwoven with walkways, the fountain was nearly half an acre in size and became a popular gathering place for events and protests after it opened in 1982. A group of black-clad women protested for peace there weekly from 2001. It was also the site of an Occupy movement encampment in 2011, and later protests after the death of Freddie Gray. Plans had called for its demolition for years, and in 2015 the final decision was made to tear it down.

Lisa Moren, a professor of visual art at the University of Maryland, was among a group of artists, architects and community members opposing the fountain’s demolition. In collaboration with the Nonument Group, she interviewed people to collect memories of the fountain and staged a series of interventions, including a march where participants launched tiny candle-lit boats. Meanwhile, the group built a detailed 3D model of the site.

The fountain was demolished in 2016, but with the 3D model and the memories gathered through interviews, Moren and the Nonument Group developed an interactive augmented reality app that enables users to use a smartphone or tablet to move through a digital version of the fountain and hear stories from people who used the site. “It’s important that Baltimore had a little piece of modernism in the 20th century,” Moren says. “These things really do diminish in memory. People really do forget what was there.”

The Nonument Group’s next project involves the flying saucer-shaped concrete Memorial House of the Bulgarian Communist party, better known as the Buzludzha Monument. Perched on a mountain in the Balkan range, a slender observation tower stands aside the hulking, round main hall in which the Communist party held ceremonies and retold its own history with a sweeping mosaic. Built in the early 1980s and abandoned only a decade later, Buzludzha has been slowly eaten away by the elements and invaded by looters and urban explorers.

This spring, Tomšič and Bricelj Baraga traveled to Bulgaria to document the site. With collaborators from the Nicosia-based Cyprus Institute, they photographed the exterior of the monument and its landscape with drones, and laser-scanned the interior. Using a surveying and data-collection process known as photogrammetry and a series of high-powered computer workstations, a team led by Georgios Artopoulos will create a digital model of the monument for use with virtual reality headsets or smartphones.

Though a guard is stationed on site to prevent looting, the original Buzludzha building is falling apart. High winds and snowy conditions have sped its decay. “My background is in architecture, so I’ve seen a lot of concrete in my life,” says Artopoulos. “This was the worst quality concrete that I have ever seen. It cannot withstand these environmental conditions.”

The Nonuments Group will stage an artistic intervention at Buzludzha this autumn, and plans to make its virtual model available to the public.

Neither Tomšič nor Bricelj Baraga are confident the building will be preserved, but they hope their work will at least help save the narrative of the space. “Even if it’s gone, as in the case of the McKeldin fountain, we will be able to preserve it digitally so people will still be able to see this beautiful structure,” says Bricelj Baraga.

- This article was amended on 1 August 2019, because while the former Yugoslavia was communist and allied with the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin, it was not part of the Soviet Union as an earlier version said.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.