Cocoons of glistening ice in Vatnajökull glacier, Iceland; geometric Fingal’s Cave in Scotland; echoey mouths of darkness in Mexico’s cenotes. All over the world, caves have inspired awe, as well as providing shelter.

This week, a slightly lesser-known site, Margate Caves, has reopened after being closed to visitors for 15 years. Campaigners have been working to save it from redevelopment since 2008, raising funds to preserve, restore and reopen it.

The caves were formed from a chalk mine dug in the 1700s. The stone was extracted by hand using iron picks, whose marks can still be seen on the cave walls. Around 2,000 tonnes of chalk was hauled out and used to make bricks and cement for local building work. Once this was completed, the caves were sealed again and left undisturbed until the 1800s when, so one story goes, they were rediscovered by accident by a gardener working for the landowner, one Francis Forster.

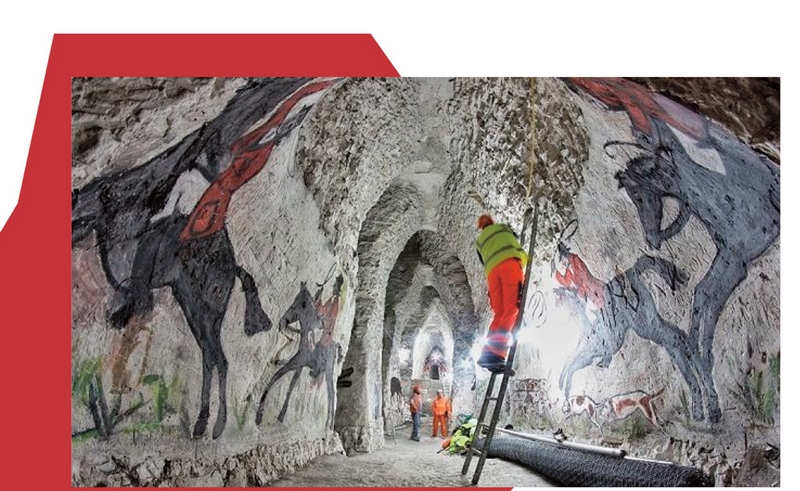

A later newspaper article told a different tale – of Mr Forster discovering the caves after he noticed that his pet rabbits kept disappearing by the roots of a pear tree. After its discovery, Forster added a stairway, and used the caves as an ice store and wine cellar. He and subsequent owners decorated the caves with murals, including a tiger, a bear and a green hippopotamus.

After Forster’s death the caves were sealed again, and in subsequent years were opened and closed as a tourist attraction by several owners and used as air raid shelters in the two world wars. They were also rumoured to have been used by smugglers bringing in contraband from the Thanet coast.

The recent conservation project has involved installing specialist lighting around the caves (which are 94 metres long and 12 metres high), restoring the artworks and building a visitor centre. The work has also led to the discovery of a new borehole, which suggests there could be a further tunnel below.

If you prefer cave art that’s a little older, Cueva de las Manos (Cave of Hands) in the Pinturas valley in a remote part of Argentinian Patagonia, has stencilled handprints dating back 10,000 years. They are some of the earliest examples of cave art, made using mineral pigments and spraying pipes. Also in Patagonia, on the Chilean side, the Capillas de Mármol (Marble Chapels) have been carved by 6,000-plus years of waves washing away softer stone to reveal the swirling blues of a peninsula of solid marble.

Hang Sơn Đoòng Cave in Vietnam, near the Laos border, is thought to be the largest cave in the world, at more than 5km long and 200 metres tall. It was discovered in 1991 in Phong Nha Ke Bang national park, and has its own jungle and river inside. Visitors can camp overnight beside the waterfall.

The twinkling Waitomo caves on New Zealand’s North Island would make for another great sleepover – except the current residents are the only ones allowed to stay the night. Also known as the Glowworm Caves, they are home to thousands of the country’s native Arachnocampa luminosa.

Caves that appear to glow in the dark can be found in many spots around the Mediterranean. Capri’s Blue Grotto is one of the best-known, but a good alternative is the Blue Cave, on the island of Bisevo near Split, Croatia. The glow is the result of the sun’s rays hitting the water and reflecting off the limestone floor.

Dreams of finding jewels inside a treasure-filled cave almost come true with the giant crystals of Naica in Chihuahua, Mexico. Some of the sparkly specimens are up to 12 metres long, but the cave lies 300 metres underground, temperatures can reach 50C (which feels like 105C with humidity of more than 90%), so it’s only visited, for short periods, by researchers in special suits. An alternative is the Crystal Cave at Put-in-Bay on South Bass Island in Lake Erie, Ohio. The world’s largest known geode, it is a single rock cavity with crystal-studded walls, discovered in 1867 by workers digging a well for winery.

With constant below-zero temperatures, Skaftafell ice cave is in Iceland’s recently Unesco-listed Vatnajökull glacier. The glacier ice was formed from water flowing down the slopes Öræfajökull, Iceland’s tallest active volcano, and contains few air bubbles, making it appear a vibrant blue.

The hexagonal basalt pillars of Fingal’s Cave in the Inner Hebrides have inspired creatives for centuries. It’s similar to Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland, and one legend has it that they were the end pieces of the bridge built by Irish giant Fionn mac Cumhaill to get to Scotland to fight his rival.

Sometimes it’s what’s inside the cave that draws visitors. Phraya Nakhon cave, in Khao Sam Roi Yot national park in central Thailand, has a temple positioned directly under a shaft of light coming from a hole in the ceiling and surrounded by trees reaching for the light.

It’s the wildlife that people come to see at the Cave of Swallows in Aquismón, eastern Mexico. It’s home to thousands of birds that fly in concentric circles to exit and enter from the surrounding jungle. It’s the world’s largest known cave shaft, around 200 metres wide and dropping 1,900 metres to the floor from its highest side.

Looking for a holiday with a difference? Browse Guardian Holidays to see a range of fantastic trips

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.