Dr. Sir,

We have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of yours dated the 3d Inst. Since it was written, the MSS. to which you refer have reached you safely, as we learn from Mr. Paulding, who has been so informed we presume by Mr. White.

The reasons why we declined publishing them were threefold. First, because the greater portion of them had already appeared in print — Secondly, because they consisted of detached tales and pieces; and our long experience has taught us that both these are very serious objections to the success of any publication. Readers in this country have a decided and strong preference for works (especially fiction) in which a single and connected story occupies the whole volume, or number of volumes, as the case may be; and we have always found that republications of magazine articles, known to be such, are the most unsaleable of all literary performances. The third objection was equally cogent. The papers are too learned and mystical. They would be understood and relished only by a very few — not by the multitude. The numbers of readers in this country capable of appreciating and enjoying such writings as those you submitted to us is very small indeed. We were therefore inclined to believe that it was for your own interest not to publish them. It is all important to an author that his first work should be popular. Nothing is more difficult, in regard to literary reputation, than to overcome the injurious effect of a first failure.

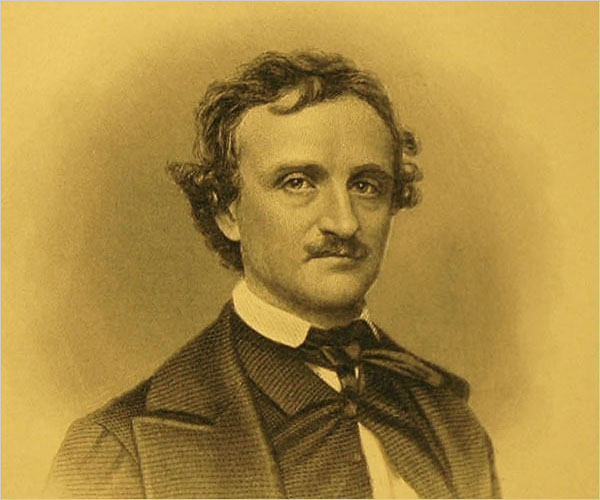

That is an extract from a letter sent to Edgar Allan Poe by James K Paulding, the representative of the publishers Harper and Brothers. It was written in 1836 – although the excuses about short stories not selling well might as well have been sent by publisher today. The only thing that really marks out this letter from more modern rejections is its length and the time and trouble that Paulding obviously took to read the stories. But that’s not to suggest that 19th-century publishers were somehow more noble or less pressed for time than today’s. Pauling goes on:

We are pleased with your criticisms generally — although we do not always agree with you in particulars, we like the bold, decided, energetic tone of your animadversions, and shall take pleasure in forwarding to you all the works we publish — or at least such of them as are worthy of your notice. We are obliged to publish works occasionally, which it would scarcely be expected of the Messenger to make the subject of comment.

The last number of the Messenger came to hand last evening, and in our opinion fully sustains the high character which it has acquired for itself. The notices of the Life of Washington, and Sallust we presume will prove highly pleasing to Mr. Paulding and Professor Anthon.

Yes, it’s safe to assume that Paulding only really went to so much trouble because Poe was at that time a popular critic. Sadly, I didn’t manage to find Poe’s reply and how he reacted to such charming cheek. That’s doubly a shame, because whatever you make of Poe’s fiction, he could write a damn good letter:

Sir, — I find myself at leisure this Monday morning, June 1, to notice your very singular letter of Saturday, and you shall now hear what I have to say. In the first place, your attempts to bully me excite in my mind scarcely any other sentiment than mirth. When you address me again, preserve, if you can, the dignity of a gentleman. If by accident you have taken it into your head that I am to be insulted with impunity I can only assume that you are an ass.

How’s that for an opening? The most pleasing thing about that letter of 1839 is that it was sent to Poe’s employer William Burton who owned The Gentleman’s Magazine. Poe signed off: “If you persist in it our intercourse is at an end, and we can each adopt our own measures.” Is he calling him out for a fight? Not surprisingly, Poe soon afterwards changed jobs.

I came across the above letters while hunting out answers for a series of questions that has cropped up frequently this month on the Reading group. Namely: How original was Poe? How in step with his times was he? How much was he writing for himself and how much was he aware of his audience? Poe himself provides most of the answers in a letter written to Thomas White (another employer and the owner of the Southern Literary Messenger) in 1835. It seems that Poe knowingly rode contemporary currents – even though he couldn’t help rocking the boat:

A word or two in relation to Berenice. Your opinion of it is very just. The subject is by far too horrible, and I confess that I hesitated in sending it you especially as a specimen of my capability. The Tale originated in a bet that I could produce nothing effective on a subject so singular, provided I treated it seriously. But what I wish to say relates to the character of your Magazine more than to any articles I may offer, and I beg you to believe that I have no intention of giving you advice, being fully confident that, upon consideration, you will agree with me. The history of all Magazines shows plainly that those which have attained celebrity … were indebted for it to articles similar in nature to Berenice — although, I grant you, far superior in style and execution. I say similar in nature. You ask me in what does this nature consist? In the ludicrous heightened into the grotesque: the fearful coloured into the horrible: the witty exaggerated into the burlesque: the singular wrought out into the strange and mystical. You may say all this is bad taste. I have my doubts about it. Nobody is more aware than I am that simplicity is the cant of the day — but take my word for it no one cares any thing about simplicity in their hearts.

The rest of that fascinating letter is contained in Arthur Hobson Quinn’s Critical Biography of the author. In it, Poe compares himself to several contemporaries, pointing out similarities of theme and intent – and suggesting that such stories are popular. Pleasingly he does admit: “In respect to Berenice individually I allow that it approaches the very verge of bad taste.” He promises not to “sin quite so egregiously again.” As if!

This month, I’ve perhaps worried enough over how well Poe succeeded with Berenice and other stories. But I should at least say that now I’ve carried on through my edition The Murders In the Rue Morgue and Other Tales I have found more to admire. There is, for instance, some admirably nasty characterisation in “The Tell Tale Heart”. That narrator is one bad man. Likewise the glimpse inside the deeply troubled mind of the narrator of “The Black Cat” was genuinely unsettling. The casualness with which he murders his wife and kills his beloved cat invoke unsettles almost as much as Patrick Bateman.

Against that I must say that Poe has real trouble with endings. The vast majority in The Murders In the Rue Morgue And Other Tales are both abrupt and daft. An egregious example comes in “The Pit And The Pendulum”. Just as the narrator is about to be crushed to death, after enduring 20 pages of baroque agonies at the hands of the Inquisition, we hear noises without, the walls that were rushing in move back and we read:

“An outstretched arm caught my own as I feel, fainting into the abyss. It was that of General Lasalle. The French army had entered Toledo. The Inquisition was in the hands of its enemies.”

What spectacular good fortune! It is possible to formulate some kind of defence of the way Poe chucks his story off the cliff. Perhaps the suddenness of the ending, and lack of detailed explanation of the rescue, is deliberately disconcerting, and provides a shock, as much as a relief, after all that has gone before. But it’s hard not to think that Poe just gave up when it came to the conclusion – which isn’t entirely unlikely, given what we know about Poe’s trouble with deadlines, drink and other demons.

In the end, I’m left with divided feelings about Poe, which seems to me to be neatly in accord with the fascinating conversation and variant opinions eloquently exressed on last week’s post .

It’s pleasing to note that Poe’s contemporaries were similarly divided. Sometimes in the same letter. No less than Washington Irving wrote to him on November 6 1839 to say:

Dear Sir, — The magazine you were so kind as to send me, being directed to New York, instead of Tarrytown, did not reach me for some time. This, together with an unfortunate habit of procrastination, must plead my apology for the tardiness of my reply. I have read your little tale of “William Wilson” with much pleasure. It is managed in a highly picturesque style, and the singular and mysterious interest is well sustained throughout. I repeat what I have said in regard to a previous production, which you did me the favor to send me, that I cannot but think a series of articles of like style and merit would be extremely well received by the public.

I could add for your private ear, that I think the last tale much the best, in regard to style. It is simpler. In your first you have been too anxious to present your picture vividly to the eye, or too distrustful of your effect, and have laid on too much coloring. It is erring on the best side — the side of luxuriance. That tale might be improved by relieving the style from some of the epithets. There is no danger of destroying its graphic effect, which is powerful. With best wishes for your success,

I am, my dear sir, yours respectfully,

Washington Irving.

The unnamed story is “The Fall Of The House of Usher”. Yes, I am quite pleased that we on the Reading group aren’t alone in thinking that Poe rather over-egged the pudding on that one. If only he had relieved some of those epithets.

Meanwhile, talking of contemporary big guns, there’s also a surviving letter to Poe from Longfellow in 1841:

You are mistaken in supposing that you are not “favorably known to me.” On the contrary, all that I have read from your pen has inspired me with a high idea of your power; and I think you are destined to stand among the first romance-writers of the country, if such be your aim.

Romance! Maybe with a corpse bride. Otherwise, it’s hard not to think that Longfellow was wrong. Although not so wrong as the critics who castigated Poe for bending the truth in “The Narrative Of Gordon Pym”. Many seem to have believed it was an attempt to describe real events. There’s a lovely example in the same Gentleman’s Magazine that employed Poe:

“A steady perusal of the whole book compelled us to throw it away in contempt, with an exclamation very similar to the natural phrase of the Indian. A more impudent attempt at humbugging the public has never been exercised … Arthur Gordon Pym puts forth a series of travels outraging possibility, and coolly requires his insulted readers to believe his ipse dixit … ”

The review is unsigned and so gloriously wrong-headed that I can’t help wonder if Poe himself wrote it as a joke. Either way, Poe has the last laugh. It’s a salutary warning against the vagaries of criticism. No matter what we may have made of Poe’s writing this month, the outstanding fact is that we and plenty of others are still reading “The Murders In the Rue Morgue” and plenty of his other stories more than 150 years after his death … I imagine he would have settled for that.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.