Nasa, Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Gulfstream scientists work to build a supersonic jet that would fly more than 2,485 mile per hour, and can fly its passengers from London to Sydney in just four hours.

The biggest obstacle scientists are working to overcome is the sonic boom that was produced by the Concorde supersonic jet.

Concorde‘s sonic boom noise level was 105 PLdB. The PLdB that researchers believe will be acceptable for unrestricted supersonic flight over land is 75, but NASA wants to eventually beat that and reach 70 PLdB.

NASA‘s aeronautical innovators are one step closer to confidently crafting a viable commercial airliner that can fly faster than the speed of sound, yet produce a sonic boom that is quiet enough not to bother anyone on the ground below.

The key to this recent advance came when wind tunnel tests of scale model airplanes verified that new approaches to designing such aircraft would work as hoped for when aided by improved computer tools, which were used for the first time together in each step of the design process.

Nuisance noise generated by a commercial supersonic jet’s sonic booms during cruise, and by its powerful engines at takeoff and landing, has kept the speedy aircraft from entering service in the United States – except for Europe’s Concorde, which was limited to trans-Atlantic flights only.

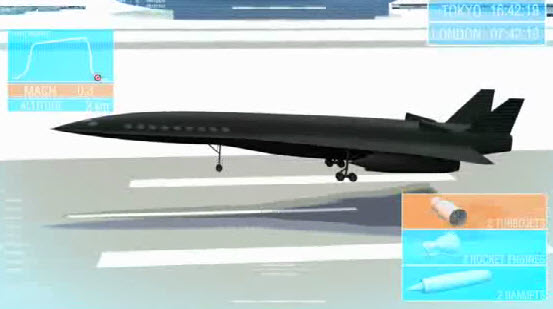

Using the computer tools, teams led by Boeing and Lockheed Martin, and funded through a NASA Research Announcement, came up with designs for two small supersonic airliners that would carry between 30 and 80 passengers and potentially enter service in the 2025 timeframe.

“In bringing their design expertise to the process, these companies are not only addressing the low boom design elements, but all of the other aspects necessary for a realistic design,” said Peter Coen, NASA’s supersonic project manager at Langley Research Center in Virginia.

For example, the computer tools show that one way to reduce the perceived loudness of a supersonic jet’s sonic boom is to change the aircraft shape, in part, by lengthening the aircraft’s fuselage, making it much more slender. Theoretically, the noise issue could be solved by a really, really long aircraft body.

Unfortunately, while an 800-foot-long airliner may lead to publicly acceptable sonic booms, an aircraft that size still must fit at its gate, make turns while taxiing to the runway without hitting anything and generally not require an expensive redesign of the nation’s airports.

And while a commercial supersonic airliner flying from New York to Los Angeles over the U.S. heartland may be another decade or two away, Coen said it’s very possible that smaller supersonic business jets could debut in the skies much sooner because lighter aircraft create weaker shock waves, which makes the low boom design challenge easier to solve.

“The business jet would probably be the first on the market, and that would help introduce some of the technologies that eventually would be used on the supersonic airliner.” Coen said.