In the centre of Copenhagen is something distinctly un-Danish. Inderhavnsbroen – the Inner Harbour Bridge, or “kissing bridge”, because of two retractable sections that meet in the middle – was due to be finished in 2013, but there were design problems and then the contractor filed for bankruptcy. It earned the nickname the “missing bridge”, a very public failing in such a well-ordered city. A revised opening date for summer 2015 was missed. It should now open this year.

The bridge will eventually link Nyhavn and Christianshavn: that is, the picturesque, rainbow-fronted city centre and a more edgy district that is home to the hippyish Christiania commune. Or, if you have come to Copenhagen for the food – which, statistics suggest, you probably have – it will provide a handy shortcut between Claus Meyer’s the Standard and René Redzepi’s Noma.

Meyer and Redzepi are the two most influential figures in the Nordic food revolution; though you can be forgiven if you are only familiar with the latter. It was Meyer’s idea that a restaurant might be inspired, rather than restricted, by the limited produce in Nordic countries. He approached Paul Cunningham, an English chef based in the city but he declined and suggested a shortlist including Redzepi, then a 25-year-old sous chef. Noma opened in 2003, with Meyer and Redzepi as partners; within two years Redzepi had won a Michelin star and the accolades have scarcely stopped since.

In Denmark, Meyer needs no introduction: he was the host of a popular TV cooking show and the 52-year-old entrepreneur now has an empire that includes books, delis, bakeries, a country hotel and high-end restaurants. The latest of these is the Standard, an art-deco building that was once Copenhagen’s Customs House and contains an informal cafe, a pan-Indian restaurant, jazz club and Michelin-starred operation called Studio. He’s also a philanthropist, working with prisoners in Denmark and in 2013 opening Gustu in La Paz, Bolivia, South America’s poorest country, with the promise, like Noma, to cook only with indigenous ingredients.

But – if you believe the gossip – the founders of new Nordic cuisine have become estranged. Redzepi told the Wall Street Journal in 2013 that he became so frustrated that he gave Meyer an ultimatum: “It’s you or me, Claus.” The discussion ended with Meyer selling a chunk of his majority stake in Noma – he still retains 20% – to an American investor and Redzepi becoming the main owner. Sitting either side of the water, failing to meet in the middle, their faltering relationship has more than a little in common with the kissing bridge.

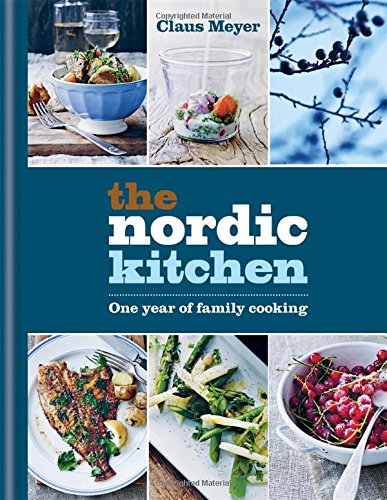

On a frigid, blue-skied morning in January, Meyer does not come across like a man with a grudge. He is a strapping 6ft-plus in a tight black T-shirt and charcoal trousers. He moved to New York City a few months ago to oversee the ambitious opening this spring of a food hall and brasserie in Vanderbilt Hall, the old waiting room in Grand Central Terminal, but he is back on a flying visit to promote his new cookbook. He has published more than a dozen recipe collections in Danish, but The Nordic Kitchen is his first in English.

Does Meyer feel that he has received the credit he deserves for helping to make Nordic cuisine so exciting? “It’s a good question,” he says, his eyes scanning from the jazz club where we sit towards Noma, scarcely 200 metres across the water. “Sometimes I think no. I felt in the beginning in New York: ‘Nobody knows me and René has got all the credit for a number of reasons.’ But in the last couple of months, I’ve really come to understand that a lot of people know who I am and recognise what I’ve been doing. They don’t underestimate my contribution.”

Relations with Redzepi, Meyer insists, are cordial and he is effusively complimentary about his invention and artistic expression: “When I met René, I didn’t see the unpolished diamond he was. I didn’t see that at all.” Meyer laughs. “So the mature answer would be to say, ‘No, I think I get the recognition I deserve.’ And I like to think René deserves much of what he gets.”

In the introduction to The Nordic Kitchen, Meyer attempts to piece together the origins of the food revolution that he helped to create. It’s a fascinating tale that takes in powdered potatoes, onanism and Lars von Trier. It is also a terrific underdog story: one not just about food, but about economic and cultural development. It is estimated that 10,000 jobs have been created in the restaurant industry in Copenhagen in the last decade. Noma – rated the best restaurant in the world four times since 2010 – had to build an elaborate rock garden outside to deter tourists from gawping in through the windows.

Meyer describes the first 19 years of his life in the south of Denmark as “a culinary nightmare, the darkest period in Danish food history”. Doctors and puritanical priests had, for centuries, lobbied against sensual, pleasure-giving food. “The idea of preparing delicious meals for your loved ones was a sin in line with eccentric dancing, abuse of alcohol, incest and masturbation,” Meyer says.

The situation was especially dire in Meyer’s home. His father didn’t want children and never loved him – he relates this information with a brisk matter-of-factness that is perhaps uniquely Scandinavian – and his parents separated when he was 13. His mother became an alcoholic and food, never a priority, became an afterthought. This only changed when Meyer went to France to work as an au pair and wound up living with a fourth-generation baker and traiteur and his wife in Gascony.

“I thought, ‘What the fuck have we been eating for 19 years?’” he recalls. “If you can eat foie gras, brioche, fresh baguette baked twice a day. In Denmark, I ate two-week-old sandwich bread full of additives and now I’ve got a baguette that made me cry with pleasure.”

The revelation was deeper than that, though. “What I learned was that if your parents cook shitty food out of shitty ingredients, well, maybe they end up living shitty lives,” says Meyer. “And kids are suffering from that. But apparently if you make the most wonderful food, then maybe life becomes great. I want to tell that story in Denmark!”

When Meyer returned to Denmark in the early 1980s, he believed his “mission in life” was to introduce French food to his homeland. After deciding there was only so much he could achieve as a chef, he earned a spot on TV and imported foie gras, truffles and olive oil. Meyer shakes his head: “Then 15, 16 years down the road, I realised I’d got it wrong.”

This is where the film-makers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, fellow Danes who created the Dogme 95 movement, came in. Believing that if they competed with Hollywood on their terms, they would always lose, they chose to operate outside the system. Meyer thinks that this, to a degree, is what he and Redzepi achieved with Noma. “We redefined the concept of luxury,” says Meyer. “We said luxury can be about a perfect leaf of dandelion picked in the right place at the right moment and treated as carefully as you would treat foie gras. Suddenly, we were able to be part of the game. That’s exactly like the Dogme brothers. Foie gras to beetroot – to me that is like Hollywood to Danish film-making! And the rest is history.”

The appetite for high-end Nordic cooking remains voracious. Soon Meyer will open in Grand Central: a 200-cover, $20m operation with 300 employees. More than 750,000 people pass through the terminal every day. “I’ve never tried anything close to it,” Meyer admits. “But if I don’t pull it off, I won’t forgive myself.”

Meyer could sound like the “serial entrepreneur” that he calls himself, but that would be misunderstanding his conviction that good food can change lives. He explains by talking about how his father loved Elvis Presley, Tarzan movies and Muhammad Ali, sometimes being moved to tears as they sat watching Elvis sing, Tarzan swing and Ali sting. They were the only happy moments they spent together. He says: “I think maybe because I wanted my father to look at me and cry because I was his son, I wanted to be like Ali and Tarzan and I wanted to create fairy tales, to do fantastic things. Maybe it’s a craving for love. Maybe I do what I do because I need people to approve of me: ‘You’re OK Claus, what you’re doing is fine, we love you.’”

Six recipes from Claus Meyer’s Nordic Kitchen

Bruschetta with squash puree and goats’ cheese

Serves 4

day-old white bread 8 slices

squash puree ½ quantity (see below)

goats’ cheese 100g, thinly sliced from a log

olive oil 2 tbsp

rosemary 1 sprig, needles picked

sea salt flakes and freshly ground pepper

For the squash purée

butternut squash 1

butter 25g

cider vinegar 50ml, plus extra if needed

sea salt flakes and freshly ground pepper

acacia honey 1 tbsp

To make the squash puree, peel and halve the squash, then scrape out the seeds with a spoon. Cut it into large cubes, put them in a pan, cover with water and bring to the boil, then simmer for about 20 minutes until tender. Drain and place in a blender along with the remaining ingredients for the puree, then blend until completely smooth.

Place the bread slices on an oven or grill rack, spread the squash puree over them and top with the slices of goats’ cheese. Drizzle with olive oil and season with the rosemary, salt and pepper.

Bake the bruschetta in a preheated oven at 250C/gas mark 10 (or your highest gas mark setting) for 3-4 minutes until the bread is crisp and the cheese is crispy and golden. Serve the bruschetta immediately while they are warm, either as a snack or as a starter with a good salad.

Pork roast with herbs, fennel and new potatoes

Serves 6

spring onion 1

rosemary 4 sprigs

sage 5 sprigs

chervil 5 sprigs

organic lemon 1

pork loin 1, boneless with skin on

sea salt flakes and freshly ground pepper

new potatoes 1.2kg

cold-pressed rapeseed oil 2 tbsp

fresh spinach 100g

fennel 1 bulb

Peel the spring onion and slice it thinly. Rinse the herbs and pick the leaves, but keep the stems for the roast to sit on. Finely grate the zest of the lemon.

Cut the pork almost in half, leaving a small portion uncut on one side so that you can open out the meat, and fill it with the herb leaves, lemon zest, salt and pepper. Close it again and tie it together tightly with kitchen string to seal all the goodness inside the meat.

Rinse the potatoes thoroughly and cut in half. Put them into an ovenproof dish together with the zested lemon, cut into quarters. Drizzle the rapeseed oil on top, season with the herb stems, salt and pepper and mix well. Put the pork on top of the potatoes and roast in a preheated oven at 180C/gas mark 4 for 1-1¼ hours until the crackling is nice and crisp and the potatoes are golden and crisp on the outside but soft in the middle. If you like, use a meat thermometer to check the temperature at the centre of the roast, which should be about 65C.

Take the roast out of the oven and leave to rest for 5-10 minutes. Meanwhile, rinse the spinach several times in cold water and leave in a sieve for the water to drip off. Rinse the fennel and then slice thinly.

Mix the fennel and spinach with the potatoes – enough to warm them a little, but not so much that they become soggy.

Carve the roast and serve with the potatoes and all the lovely greens.You don’t really need any other accompaniments, as you have everything in one dish. Once you have put the meat in the oven, the work is done and dinner is on its way!

Fish soup with root vegetables and broad bean mash

Serves 4

For the soup

apple 1 large

leek 1

parsnip or parsley root 1

onion 1

garlic 3 cloves

bones of flat fish, such as flounder, halibut or turbot 1kg

parsley stems a few

whole black peppercorns 12

white wine ½ x 75cl bottle

whipping cream 50ml

wheat beer 50ml

cider vinegar 1 tbsp

sugar to taste

For the filling

carrot 1

celeriac 100g

water 50ml

sea salt flakes

cooked dried broad beans 100g (or use tinned beans)

olive oil 2 tbsp

organic lemon grated zest and juice of ½

freshly ground pepper

parsley ¼ handful, chopped

First, make the soup. Wash the apple (keep the peel on) and vegetables, then cut them all into small pieces and put in a pan along with the fish bones, parsley stems and peppercorns. Pour over the white wine and add enough water to cover the vegetables. Bring the soup to the boil and skim off any foam and impurities, then lower the heat and simmer for 25 minutes.

Turn the heat off and leave the soup to stand for 20 minutes, then strain through a sieve and return to the pan. Add the cream and then reduce to the desired intensity and consistency. Season with the wheat beer and vinegar, and sugar, salt and pepper to taste.

Now make the filling. Peel and cut the vegetables into large cubes. Put the vegetables in a small pan with the measured water and some salt. Steam the vegetables, with the lid on, for about a minute until tender but still al dente.

Mash the beans coarsely, adding the oil, lemon zest and juice, and salt and pepper to taste.

Pour any excess water from the steamed vegetables into the soup, then add the mashed beans to the pan along with the vegetables and let it all warm through.

Serve a large spoonful of vegetables and mashed beans in shallow soup dishes. Whisk the soup quite vigorously with a whisk so that it is lightly foaming, then pour the hot soup over the vegetables and finish with a sprinkle of chopped parsley on top. Serve with good bread.

Risotto with oyster mushrooms and spinach

Serves 4

chicken stock or water 1 litre, plus extra if needed

shallot 1

butter a little, for sautéing

pearl barley 300g

white wine 100ml

sea salt flakes

fresh spinach 100g

mixed mushrooms 150g

butter 30g, diced

parmesan cheese 50g, freshly grated

freshly ground pepper

organic lemon finely grated zest and juice of ½-1

Bring the stock or water to the boil in a saucepan. Peel and finely chop the shallot, then sauté it in a little butter until it is translucent and tender but without colouring.

Add the pearl barley and sauté for a few minutes, then add the white wine and allow the barley to absorb it. Add the boiling stock or water a little at a time so that the barley is constantly just covered, stirring as you go. Leave the pearl barley to cook for 15-18 minutes until it is soft but still with a little bite to it. It is important to season with salt during the cooking so that it is absorbed by the pearl barley (but not too much if your stock is very salty).

Wash the spinach thoroughly, place the leaves in a colander and leave it to drain. Shred the spinach using a sharp knife.

Clean the mushrooms with a brush or small vegetable knife and cut them into small pieces, then fry them in a little butter in a pan for 3-4 minutes. Season the mushrooms with salt and pepper, then mix them into the pearl barley (saving some for the garnish).

Remove the pearl barley from the heat and stir in the diced butter and grated parmesan to create a smooth and creamy consistency (you may want to add some extra stock or water to get the right consistency). Add the fresh spinach to the hot risotto so that it softens a little, then season to taste with salt, pepper and the lemon zest and juice.

Serve the risotto with the reserved fried mushrooms on top and eat it straight away while it remains soft in texture and the barley is still al dente.

Fried flounder with braised chicory

Serves 4

flounders 2 whole or 8 fillets

sea salt flakes

chicory 4 heads

rapeseed oil 3 tbsp

unrefined cane sugar 2 tbsp

orange juice of 1

cider vinegar 50ml

apples 2

freshly ground pepper

parsley ½ handful

If using whole flounders, rinse and clean them, making sure that they are free of blood and mucus. Cut out the fillets and skin them (or get your fishmonger to do the work for you). Save the bones for making stock, soup or sauce.

Cut the fish fillets in half, place in a dish and sprinkle with salt, then put them in the refrigerator while you make the braised chicory.

Halve the chicory heads, rinse them in cold water and drain them well. Heat 1 tablespoon of the rapeseed oil in a sauteuse pan. Add the chicory halves, cut side down, and fry for a few minutes so that they have a beautiful golden crust. Flip them over, sprinkle with the sugar and leave to caramelise slightly (watch out that the sugar doesn’t burn).

Add the orange juice and vinegar and simmer for 4-5 minutes until the chicory has absorbed about half of the liquid.

Wash and core the apples, then cut them into small cubes. Add them to the pan and simmer with the chicory for 30 seconds. Toss around to mix well, and season with salt and pepper. Finely chop the parsley and sprinkle it over the chicory, then round off by drizzling over 1 tablespoon of the rapeseed oil.

Fry the flounder fillets in the remaining tablespoon of oil in a hot frying pan for 1-2 minutes on each side until they have a beautifully golden and crisp crust.

Arrange the chicory on 4 plates – 2 halves on each plate – and serve the fried flounder on top of the chicory. The chicory can also be served by itself as a small dish or as a side to fried poultry.

Rhubarb cake

Serves 8

For the cake layers

organic eggs 4

sugar 125g

plain flour 150g

baking powder 1 tsp

butter for greasing

For the rhubarb compote

rhubarb stalks 300g

lemon balm 1 handful of

vanilla pod ½

unrefined cane sugar 150g

To assemble

blanched almonds 50g

white chocolate 50g, plus extra shavings to decorate

whipping cream 500ml

rhubarb stalk 1

sugar a little, for sprinkling

First make the cake layers. Beat the eggs and sugar together in a bowl until pale and foamy. Mix the flour and baking powder together and sift into the batter, then fold in gently with a spatula.

Grease a springform cake tin, about 22cm in diameter, with butter and pour in the cake batter. Bake the cake in the centre of a preheated oven at 200C/gas mark 6 for about 30 minutes.

Remove the cake from the oven and leave to cool in the tin on a wire rack. When the cake is completely cool, carefully cut horizontally into 3 equal layers with a sharp knife.

Now cook the compote. Cut off the tops and bottoms of the rhubarb stalks, but be careful not to remove the white “foot” of the stalk, which is where the rhubarb flavour is most concentrated and best.

Rinse the stalks in cold water, cut into 1-2cm pieces and put in an ovenproof dish with the lemon balm. Split the vanilla pod lengthways, scrape out the seeds and mix with a little of the sugar, making them easier to distribute in the dish.

Mix the vanilla sugar into the rest of the sugar, then sprinkle over the rhubarb. Stir well and add the pod to the dish.

Bake in a preheated oven at 150C/gas mark 2 for 15-20 minutes until the rhubarb is tender but still has a firm bite. Remove the dish from the oven and leave the compote to cool completely.

Chop the almonds and white chocolate roughly. Whip the cream, set half aside for decoration and gently fold the almonds and chocolate into the other half. Add the rhubarb compote and fold in.

Assemble the cake with the flavoured whipped cream between each layer, and finish by decorating it with the pure whipped cream – for the best effect, use a piping bag.

Another decorative trick is to create rhubarb shavings by running a vegetable peeler lengthways along a rhubarb stalk. Toss the shavings with a little sugar before scattering over the cake and finish with shavings of white chocolate. OFM

The Nordic Kitchen: One Year of Family Cooking by Claus Meyer is published on 7 April by Mitchell Beazley, £25. Click here to pre-order a copy for £20 from the Guardian Booskhop

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.